PART TWO

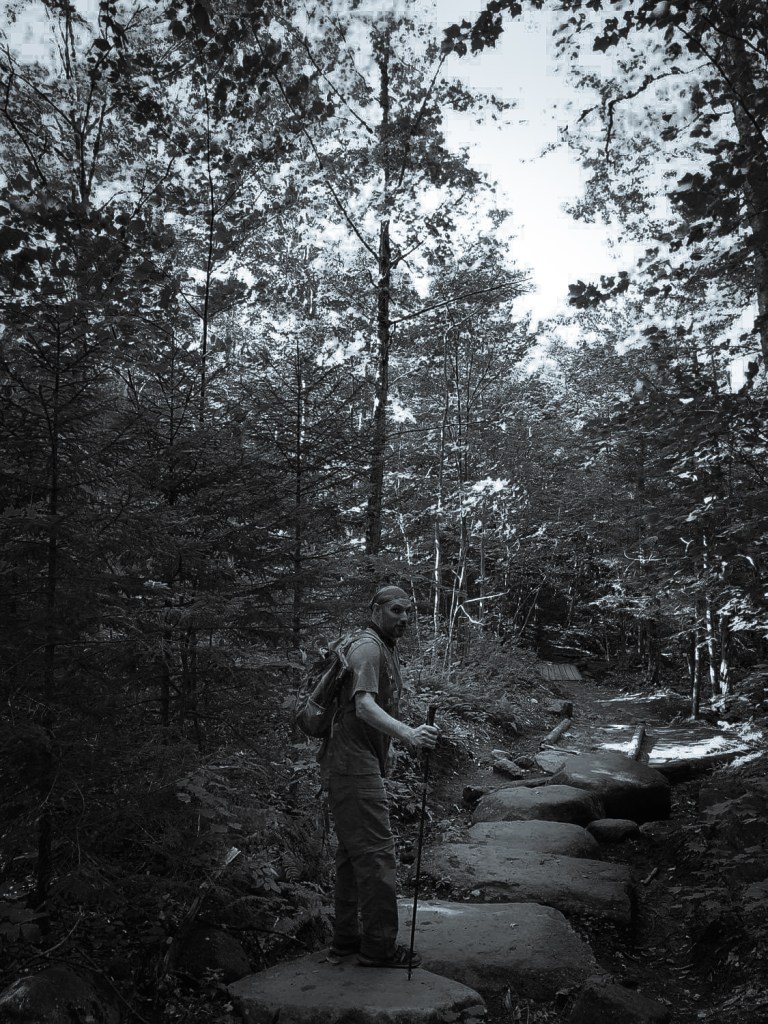

Early on in our relationship, Edwin and I went with a group of friends to the Adirondack Mountains for eight days to camp, hike, and backpack. But mostly, we went to hit up Trap Dike: a bushwhack, rock scramble, and rock climb combo.

The Trap Dike, Photograper: Carl Heilman

Preparation had been a short video that Edwin sent to each of us. It was set to encouraging, upbeat music suitable for a leisurely kayak float, and they did not film any of the more difficult portions. Everyone maintained relaxed smiles and it appeared easy enough for the average hiker to tackle . If you find this video on the internet, do yourself a favor and be assured that it is not an accurate representation of the Trap Dike experience.

*Here are some links to videos that offer a better synopsis if you’re interested:

https://youtu.be/Tu90cvcWJPw by Brian_Hikes_All_Day

https://youtu.be/MYF1_RQhVLA by Mountain Life 603

https://youtu.be/owvw2bBbZC8 by Seth Baker

We had to play scheduling by ear based on the weather. Any inclement rain could wash out the ‘trail’ altogether, and us with it. The best day to set out happened to be our last, and it promised to be a warm one. The morning began with a two-mile jaunt on Van Hoevenberg Trail to Marcy Dam.

Historically, there have been countless, temporary dams built across Marcy Brook to create a large reservoir into which timber could be rolled for annual log drives. The water would swell, threatening to overtake its confines, and a mass of logs would bump against one another until the dam was dismantled and they could become something more akin to behemoth trout, bucking and heaving their way to the mills that had been built downstream. Many a man lost life and limb while ‘birling,’ the task of riding a rolling log downstream to help prevent jams. Birlers preferred Croghan boots with studded metal calks in the soles and heels for digging into logs. They would stand atop their mounts, balancing precariously and attempting to keep from falling into the churning timber.

Logging the Adirondacks, 1901-1921 New York State Archives

Adirondack logging was outlawed In the early 1900s, and the last dam placed across Marcy Brook was never removed when the site was abandoned. The reservoir became a fixture, earning the name Marcy Dam Pond, the area a destination for those who sought a spectacular view of three of the Adirondack’s iconic peaks, Marcy, Colden, and Algonquin. It also served as a base camp for those seeking access to the hiking trails that led into their heights, a welcome respite before and after a climb.

When the old dam fell into disrepair (it was never intended to be permanent), it was rebuilt with a wooden footbridge connecting the two sides of the pond, standing for years until 2011’s Hurricane Irene and her heavy rains. Marcy Dam and its famous bridge were declared a loss by state officials. To rebuild, it would have to meet ‘modern standards,’ a several million-dollar demand. The explanation of unaffordable expense satisfied most of those locals whose nostalgia had left them ‘heartbroken’ and lobbying for repair. But officials had another reason for abandoning the dam.

“There is a man-made structure… in the middle of a wilderness that was not functioning well,” said Dave Winchell, spokesman for the area.

“The views of the peaks will still be there. You’ll see them from a trail. And in (the pond’s) place…you’ll see a natural wild trout stream. And very hopefully wild trout will be able to reach their former headwaters, which is really an exciting prospect,” said Dan Plumley from Adirondack Wild.

John Sheehan of the Adirondack Council added, “This will not be seen as a drastic or unwelcome change by nature.”

A remaining piece of the old Marcy Dam, Photographer: Myself

So, Marcy Dam Pond drained away, its famous reflection made miniature in the brook that now flows across the site. The five of us sat on stones and bits of dam corpse, surveying its remaining bones, stained by thousands of gallons of tannin-laced water and sunlight. I liked the idea of real trout swimming through its ribcage. Looking out across what had been a lakebed, grass had begun to grow, miniature savannahs atop plateaus of sediment. The brook split into small and large branches, chattering over and between smooth stones. Nature was redecorating.

Marcy Brook, Photograper: Myself

The old lake bed. Photographer: Hope

After sharing a few snacks, we crossed a small bridge that had been placed downstream in a less flood-prone area and stepped onto Avalanche Pass. The trail sloped upward along an old creek bed. Megalithic stones and cliff sides created intermittent hallways and obstacles. Rag, Map, and Ribbon Lichen festooned their surfaces in chaotic patterns of seafoam, chartreuse, and sage green.

From Left: Edwin, Tim, and Tyler. Photographer: Hope

Boardwalks being overtaken by moss. Photographer: Myself

Tim on Avalanche Pass, Photographer: Hope

Knobby-kneed roots rose from the mud to become thin things that spread and tangled over the ground like ropey hair.

Hope, Tyler, and Tim, Photographer: Myself

Me on the boardwalks. Photographer: Hope

The forest parted at last, and sunlight streamed onto the banks of Avalanche Lake. They were littered with driftwood and mountain trash, but we weren’t looking at the ground anymore. Water flowed in a rippled line between the twin towers of Avalanche Mountain to the west and Mount Colden to the east. Trees upon trees dug their roots into the banks, clung to stone walls, and sat atop ledges. They had descriptive names like Mountain Ash, Sugar Maple, Quaking Aspen, Yellow Birch, and Pitch Pine. These names seemed to convey a personality, and it was easy to imagine them coming to life and wandering up the peaks for secret meetings in the night. They would, I think, speak a language of movement and odd music, their creaks, groans, whispers and rasps echoing over the water and stirring up tales of the bogeyman.

Avalanche Lake, Photographer: Myself

“Well, holy shit. That lake is beautiful!” exclaimed Hope. The soundwaves of her Ohio-heavy accent spread across the landscape. Her features are delicate, almost doll-like, but Hope is as rough and tumble as they come.

Edwin surveyed Colden’s cliffs, scanning their length with the special sort of longing that he reserves for bad ideas. “It would be awesome to side-climb that all the way to the base of Trap Dike,” he said.

My toes curled up in my minimalist shoes and I chewed on my lip. We weren’t going to try that, were we?

“Screw that!” Hope said, laughing. “That thing is crazy!”

I’d never felt more grateful to Hope, because with Edwin, you never know.

Avalanche Lake, Photographer: Hope

In ‘Guide to Adirondack Trails: High Peaks Region,’ Tony Goodwin described the next section along Avalanche Lake as “probably the most spectacular route in the Adirondacks.” Hiker Jonathan Zaharek said it a different way,

“You know, I look at how this was carved out, and it makes me think…I feel like this is where the glacier got constipated, and it had to just jjcchhhhuuuuu!…Right through this valley. And we got this lake because of that!”

From Left: Hope, Edwin, and Me, Photographer: Tyler

Fallen boulders littered the base of Avalanche Mountain, and we scrambled through the maze they created, aided by ladders and boardwalks. Two spans of catwalks protruded from the stony face of the mountain, hovering about four feet over the lake. They colloquially became known as ‘Hitch-up Matildas.’ In 1868, Matilda Fielding, along with her husband and niece, hired Edgar ‘Bill’ Nye to lead them on a hiking tour of the Adirondacks. Nye was a comedian and avid outdoorsman, and, when they arrived at Avalanche Lake, he carried Matilda on his shoulders around the western edge, her skirts hitched up as she clung to him.

From Left: Tim, Hope, Tyler, and Edwin on one of the Hitch-Up Matildas. Photographer: Myself

The second Matilda had developed a bit of an outward lean, and from this vantage point, we could look across and see the colossal rent that was Trap Dike. Even this close, it seemed more like a vague idea than a solid, climbable reality.

Trap Dike across the lake. Photographer: Hope

Bull, Northern Leopard, and Pickerel Frogs gave off vibrating croaks from the lake’s overgrown and mucky tip. Each of these frog varieties are lithobates palustris from the Greek lith, meaning ‘stone,’ and bates, meaning ‘one that haunts.’ Palustris is Latin for ‘in the marsh.’ Added together, you have the ‘stone one that haunts in the marsh,’ the most romantic title for a frog I can imagine. We filtered water here for the last time, sitting on logs and stones and breathing deeply. I think I would have happily turned around at this point or stayed and attempted to catch and identify those lovely frogs, but I wasn’t about to be the only one to bail.

Don’t be a scaredy cat, I told myself.

The far end of Avalanche Lake. Photographer: Tyler

After a moment of searching, Edwin found one of the nearly hidden herd paths on the eastern side. It was an overgrown tangle of branches and scrub brush, and after scrambling, ducking, and weaving, we exited onto centuries of avalanche debris. A pair of stone sentinel walls faced the lake shore on either side of a ruined staircase of gabbro and anorthosite that could have been carved by dwarves or ogres. Jagged lines of blue-grey plagioclase crystals wove through the stairway, and the walls themselves contained garnet veins that were the deep red of venison or the rust of old blood.

Garnet Vein in Gabbro, Photographer: Unknown

A Plagioclase Crystal, Photographer: Sascha Gemballa

It would be 0.8 miles and three thousand feet of elevation gain from here to the summit, with half of that being the slide. From down here, it didn’t look so bad.

***

Since that day, I’ve read numerous articles on Trap Dike, and all of them have this advice:

“If you cannot routinely scale a V4/V5 at the climbing gym, this is not for you.”

“We do not recommend free soloing the Trap Dike unless you are comfortable with exposure, are not afraid of heights, and have had sufficient training and experience climbing vertical rock and steep slabs.”

“This is the most dangerous hike in the Adirondack Mountains.”

And my very favorite:

“A fall on Trap Dike could, and has, resulted in severe injury or death.”

My climbing skills at the local gym are a solid and mighty V1, maybe a V2 on a good day.

***

This image belongs to Google.

We began our ignorant ascent, bounding up and over rocks and boulders. Hairy moss and dry grasses grew in patches of loose dirt and gravel. Water wept downhill to our left, and we avoided slippery splash zones, weaving from shade to rare patches of sunlight that warmed my skin. I was glad I’d worn shorts, leaving my legs free to bunch and stretch as needed. Handholds were plentiful, and after what felt like the first real bit of climbing, I allowed myself to wallow in a sense of accomplishment. Maybe I wouldn’t be exactly comfortable at this height, but I didn’t feel phobic.

From Left: Edwin, Hope, and Tyler at the Base of Trap Dike. Photographer: Myself

Maybe a quarter of the way up the dike, we veered into a dusty incline to avoid a larger section of waterfall. The ground slid beneath our feet with every other step, pebbles skidding to the edges of stones and off of blades of dry grass where they bounced down and down and down.

“Son of a biscuit!” Tyler said. Hope’s other half, Tyler is a classic, all-American boy with Pittsburgh engraved in his every syllable like the steel it’s known for. His ‘curses’ would be solidly at home in the heart of the Bible Belt, and I’ve always enjoyed watching him exclaim, “Hope! Not in front of the kids!” at our weekly ultimate frisbee games after she’s riffed off an absolute spree of f-bombs.

My calm somehow improved with these tame epithets, and blossomed further when Hope exclaimed, “What the hell are we doing up here? This is a hike for people with nothing to lose! This is stupid! I’m not going up this thing first. Someone else go.”

In a plucked-up state, I offered to plow ahead. When others are in crisis, my mind goes into this sort of numb, detached place in order to problem solve. I think it’s just what happens when you’re a mom, like a biological switch that flips the minute you give birth. I scurried up on all fours, trailed by the others and delighting in the view-blocking shrubs around me. No one noticed Edwin fall back. He’d decided to go around our boring route and skirt the promontory for a bit of extra climbing. He moved hand over hand, but when he rounded the stone’s edge, he was met with a sheer cliff face. Climbing back and down wasn’t a safe option, but neither was going forward. Edwin weighed his options and settled on following through with his plan. He picked his way over what had become a V5 free solo, his day pack suddenly an awkward encumbrance. He looked down, and for an instant, he could picture himself falling and hitting the rocks below like a piece of meaty scree. He imagined that we would all wonder where he was, and when we went to look for him, we’d find him dead or dying. He tightened his grip on the stone before reaching one arm out, his fingers feeling for the next hold. Maintaining three points of contact at all times, he followed his arm with a foot, and he wished he were wearing climbing shoes. By the time he made it across and caught up to us, he was already over it and smiling that classic Edwin smile. It’s a mad rectangle of teeth, like a kid cheesing.

Edwin’s father offered up few compliments and little approval while he was alive. The rare deviations from that pattern almost always followed a risky move. Caving, whitewater rafting, dangling from heights – this is where they bonded. One of the first things Ed senior ever said to me was, “I’m an adrenaline junkie. I’m not afraid of anything.” Those words were repeated again and again, almost every time I saw him. If Edwin wanted love, he could get it by being the closest one to whatever edge the two of them bordered, and his father would say, “That’s my boy.” Sometimes I wonder if Edwin is still looking for love when he risks himself this way. From his dad or from a world that hasn’t always been kind. Like, maybe if he does a handstand on a crumbling cliff four thousand feet in the air, the universe will say, “That’s my boy.”

Edwin, Photographer: Myself

Tyler laughed with relief and amusement, and Hope seemed to relax, leaning back against the trap’s side. Tim merely shook his head. He’s a quiet man, ready with the occasional sarcastic crack or perfectly timed side-eye, and in the mornings, I know that if I don’t see him stoking the fire that he’ll be inside his tent, reading. The group’s return to ease resulted in the flooding back of my own discomfort; my dubious superpower lost. I must admit, in that moment and several others, that I selfishly wished at least one other person would fall apart so I could return to my functional lobotomy.

From Left: Myself and Tim. Photographer: Tyler

By the time we reached the first V4, my limbs were getting watery. I wasn’t tired; I was scared. I froze halfway up, my arms wrapped around a boulder, clinging to hand holds that I knew were perfectly safe, but felt too far apart.

I hate this, I thought. I glared at the rock, my eyes less than an inch from its surface. I hate you. I hate your rounded surface that makes me feel exposed and vulnerable. I hate your height and your position on these wretched ogre stairs that allows me to see the puddle Avalanche Lake has become from this distance.

I made pathetic whimpering sounds while Tim grabbed hold of my foot, pushing it into the rock and guiding me upward. Edwin offered encouragement from above and Hope offered advice from below. I wanted to refuse the whole thing, like a kid at the dinner table who wouldn’t eat her nasty squash casserole. It’s not so much that I’m afraid of heights. I’m afraid of myself near heights. My body and mind experience an awful sort of disconnect, and in between the two is firmly wedged L’appel Du Vide, The Call of The Void.

Associate professor of psychology at Miami University, April Smith, says that The Call is experienced in differing degrees by about 50% of the population, and is a result of the brain miscommunicating with itself. She believes that our minds set off an alarm when in a state of perceived danger, telling us to increase awareness, to perhaps step backward or forward to better observe our situation. We then analyze this step and assume that it was a desire to self-destruct. This is not so, she assures. The Call is nothing to worry about. This leads me to believe that April has never felt L’appel Du Vide herself. If she had, she would know that the Call feels less like a helpful alarm and more akin to Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, the Zombie-Ant Fungus.

These cordyceps begin as a single celled organism, invading a host ant’s bloodstream where it will begin to replicate. They then build tubal bridges that allow them to connect, communicate and feed one another until they can grow into a network that slithers from muscles and joints to surround the brain. The ant’s consciousness, whatever such a thing may be, remains intact as a hostage observer. Its body is corrupted and subverted until this living puppet is forced to climb up and away from its community. Its mandibles will permanently lock onto the vein of a leaf, rooting it wherever humidity and temperature provide the optimal atmosphere for fungal birth. A pale, fleshy tentacle will slowly begin to emerge from the base of the ant’s head, growing until it is mature enough to support a globular capsule filled with hundreds of spores that rain down upon the colony below.

Zombie-Ant Fungus, Photographer: Unknown

Here, on Trap Dike, I could feel my muscles jerk under the influence of my own personal zombie fungus. The urge to push away from the safety of my colony and seek out extinction was an awful thing. I bit the inside of my cheek to tether myself to the moment and forced myself to climb. When I made it to the top of the first crux, I saw the rest of our group exchange uneasy glances. I knew they were (understandably) wondering what they would do if I seized up on the mountain. It’s not like they could carry me. After a few awkward moments, Tim forged ahead, Tyler and Hope following close behind. They didn’t look back as our small groups gradually separated, and I felt the loathsome shame of being the weak link.

Edwin on one of the more level areas of the dike. Photographer: Tyler

Edwin jumped from rock to rock beside me, saying, “I love this! It’s absolutely perfect. I’m so glad we came!”

I looked at him, blinking slowly, and tried to muster a feeble smile.

The rest of the climbs weren’t nearly as terrifying and only plucked at the edges of my fear instead of tearing it wide open. Even the second crux, a steep forty-foot waterfall, bothered me less, though if I had known its history I may have felt differently.

***

On September 20, 2011, a hiker named Matthew Potel was leading a climb up Trap Dike with 7 members of the Binghamton University outdoors club. Two women in the group were having trouble climbing up this crux, and Potel went back to help. He managed to get one of them up and over, but as he was reaching for the last person, he lost his footing and fell 25 feet to land headfirst in the ravine. He suffered a major cerebral hemorrhage on impact. Some members of his party were able to make a call from the slide, and local rock climbers helped the Forest Rangers recover his body. He was twenty-two years old, and a 46er – having summited all 46 Adirondack peaks taller than 4,000 feet.

On March 16, 2022, 63-year-old Thomas Howard parked his car in the Adirondack Loj lot and entered his name into the trail registry alongside his intended destination – Mt. Colden via the Trap Dike. He had summited Mt. McKinley, Huascaran, Xixabangma Peak, and Mt. Kenya. He had hiked the entirety of the Appalachian Trail, the 273-mile-long trail in Vermont, and crossed the White Mountain Presidential Range in one day. Twenty-seven rangers in sled and foot operations and state police via helicopter searched tirelessly for three days before they found him at the base of the upper waterfall. He was buried beneath 4 feet of snow from a suspected avalanche.

Trap Dike Search and Recovery, Photographer: Howard DEC

There have been others, of course, but deaths are rare. Far more common are rescues, and the causes are varied: injury, exposure, lack of preparation, and paralyzing fear.

***

The first and older of the two slides appeared on our right. It was varying shades of grey and beginning to grow over. This had been the preferred route up until the same hurricane that took out Marcy Dam also created the Irene Slide. Lying ahead, she was a fresh white anorthosite – the same calcium rich stone thought to make up the crust of Earth’s moon. A crack ran up and across her surface, and I set my hands into this narrow hold, bringing my body as close to the her as I could manage. I thought about lifting my feet up and bracing them against the slide, and I tried this move a few times. They slid down. I was too afraid to lean away and provide enough pressure and friction to hold my feet against the grippy anorthosite. I put my feet up and down, flummoxed.

The Irene Slide Begins, Photographer: Tyler

Tim, Tyler, and Hope were long gone, and Edwin had had to choose between mapping out our route and staying behind to be my support system. He stayed behind and made a step for my foot out of his bent leg.

“Love, you can’t go back,” he said. “You have to go forward. That’s the only way out of this.”

There is no try, only do. I remember thinking that my Yoda was very annoying, and I decided that didn’t want a mentor anymore. I wanted Edgar ‘Bill’ Nye with his convenient shoulders and lakeshore comedy. I wanted anything but this relentless climb.

I’m pretty sure that I snarled and growled my way up, gripping the mountain’s pebbled side with my knees and feeling skin tear away. The feeble smile I’d mustered half an hour ago became an awful, painted-on thing. My teeth were clenched, and a string of endless profanity ran through my head. I was furious. This mountain and I were not friends. As we ascended, the exquisite MacIntyre Range came into full view at our backs, but my world had shrunk down to nothing more than the rock in front of me.

Tyler and Hope on the slide. Photographer, Tim

At the earliest possibility, I darted into the miniature forest that clung to Irene’s left side. Thick, low pines, scrappy bushes, and spiked deadfall created a matted tangle called ‘cripplebrush.’ I grasped at branches and trunks, pulling myself through the tangle. Blood ran down my legs now, smearing white branches when they slap-scratched against my skin. They looked like wolf teeth, and I felt a sort of raging satisfaction. Irene might be snapping at my heels, but she wasn’t going to take me.

I moved in and out of these jaws, venturing onto the slab only when the cripplebrush became too thin and loose. It was an erratic pattern, and my adrenaline crutch dwindled along with my somewhat dramatic commitment to victory. I started to feel like a blown deer, capillaries bursting in my nose and misting the air with red droplets. I was being run down, and all I wanted to do was sleep, the shrieking of my exposed nerves acting as a bizarre white noise machine.

None of that, I thought, and I imagined kicking out with sharp black hooves against Irene’s pale wolf hide, force-feeding the image to myself until it could become fuel.

“Hey, take my picture,” Edwin called out.

My head swiveled and I stared at him. Seriously? How was I to stay feral enough for survival while doing something so… mundane? I pulled out my phone with one hand while the other clung to a blackened pine root. This modern and thoroughly useless item looked ridiculous in my hand. I snapped some photos, and he said,

“Not that angle. You won’t really be able to see how steep it is. Can you turn the phone and get down low?”

Of course, dearest, I thought. Anything for you. I got what I thought might be something workable. It was hard to care while my head had rested blissfully on a patch of moss. I jerked up before the spongey mass could become a long-term pillow. I could tell that dirt had stuck to the side of my face and pieces of loam hung in my hair, swinging like spiders on silk. Sarcasm spent; I considered my husband. Was I ruining this adventure for him? He took a few easy steps and paused to look out over the rippling landscape. He exclaimed over the varied, splendid features of my foe, and pointed out peaks and waterways. I decided that this meant it must not be ruined.

Edwin on the slide. Photographer: Myself

I envied his fearless abandon, but I was also sort of proud of it. It’s a sumptuous thing to admire one’s mate, and not everyone is so lucky. Edwin had poured countless hours of his life into understanding the human body the way a geologist might understand the formation of the slide we now climbed. His movements were efficient, smooth things. He didn’t worry about falling, because if he did, his body would know what to do, where to tuck and where to spread to create the best possible outcome. He trusted it in a way that was foreign to me. I smiled my first real smile in what seemed like a very long time, and he smiled back.

I borrowed this photo of Matt McNamara coming up the slide, because I didn’t get anything that felt as though it truly captured the steeper grades. Photographer: Josh Wilson. I hope they don’t mind!

A spot to rest before continuing up. Photographer: Tyler

Irene’s final assault was hurled when the climb was nearly over. I was forced once again out of my chosen hell and back onto the slide where it had not only become steeper, but slick from the water that seeped out of Colden’s crown. I thought about how this would be the worst place of all to go down, and allowed myself a moment of panic before moving on. It was only about ten feet up and another seven across to the goat path that led to the Mount Colden Trail.

Tim, Tyler, Hope sat waiting there for us, and I settled in beside them, shocked that the worst was over. It made me feel a little bit better to learn that Hope had reached the peak and immediately vomited into a patch of huckleberry bushes. I listened to her story with my gory legs stretched out. No hooves. No fur. Just human things.

On top of the Irene Slide. Photographer: Myself

Hope fell silent, and we watched a couple make their way along the official trail. An American Labrador trotted beside them, its pink tongue lolling. It sniffed the air and began to rummage through the brush. I don’t know why we didn’t warn them about what was obviously about to occur. We just watched like a quintet of mutes as it reached THAT SPOT and began to gulp and slurp Hope’s stress-purge with cheerful abandon.

“Oh,” Hope said finally. “I puked there.”

The male half of the couple dragged back on the leash in horror as the Labrador fought to return to its feast. The three of them struggled downhill, trotting and tripping over themselves in an effort to leave us behind.

“It was a well-balanced breakfast!” Hope called after them. “Apples’n oatmeal! Probably not that bad for ‘im.”

They didn’t look back or respond. Edwin loped off to tag the peak of Colden, and I creaked my way into a standing position to follow him before we began our six mile descent to the car. We passed a group of hikers who had been up the Trap Dike just before us in matching t-shirts, climbing helmets, and coiled circles of rope slung over their shoulders. They looked very prepared. Everyone we passed stared at my legs, and several people asked if I was ok. I nodded.

“I’m fine,” I lied.

The Mount Colden Trail is thin, often slippery, and boulder laden. I noticed my left knee twinging with each down-step and climb. Twinging became pulling, and pulling became serious pain. I had been so tense going up the slide that my seized muscles were now pulling on ligaments and tendons, telling me that they’d had enough.

Back to the easy Van Hoevenberg Trail. Photographer: Tim

I hobble-hopped the miles back with Edwin’s help. I don’t really remember the drive home, but I remember the shower at Edwin’s friend Otto’s house. The water stung, and I set the heat up high enough to turn my skin a bright pink. I remember a note tacked to Otto’s refrigerator that said, “If Lena’s ok, you’re ok.” Lena was eight years old, and Otto had gone through a difficult divorce and custody battle. I stared at the note for what seemed like a long time. I felt it in my bones. I remember nestling into a down blanket by our campfire as the sun set and feeling hollowed out and glazed over. I remember thinking I would fall asleep so fast, and then laying in my sleeping bag, listening to Edwin snore, my legs contracting like they were still trying to climb, to run. A skunk nosed somewhere in the wooded back lot, and crickets scraped out their rusty songs. The nighttime cries of frogs and the whisper of trees would be lifting from Avalanche Lake to flow through Trap Dike and over the Irene Slide right now. All of that fresh white anorthosite would be gleaming, the moon’s little sister. I found myself wanting to go back there to soak my legs where waterfall trickled into lake like a pack’s worth of chilly wolf tongues. My hatred for that space had been nothing more than a hatred for my own pain. I think what I really wanted was to say thank you to the mountain that had watched me struggle 50 times, ignored my complaints and commanded me to rise, shake off the dirt and doubts, and continue.

Instead, I curled onto my side and pushed my nose against Edwin’s shoulder. It was warm under his Long Johns. I draped one arm over his chest. My breathing slowly shifted to match his and I fell asleep to the feel of his heart beating under my fingers, each of us inhaling the Adirondack air.

Edwin and I enjoying our last wade into the cold Adirondack water. Photographer: Jamison