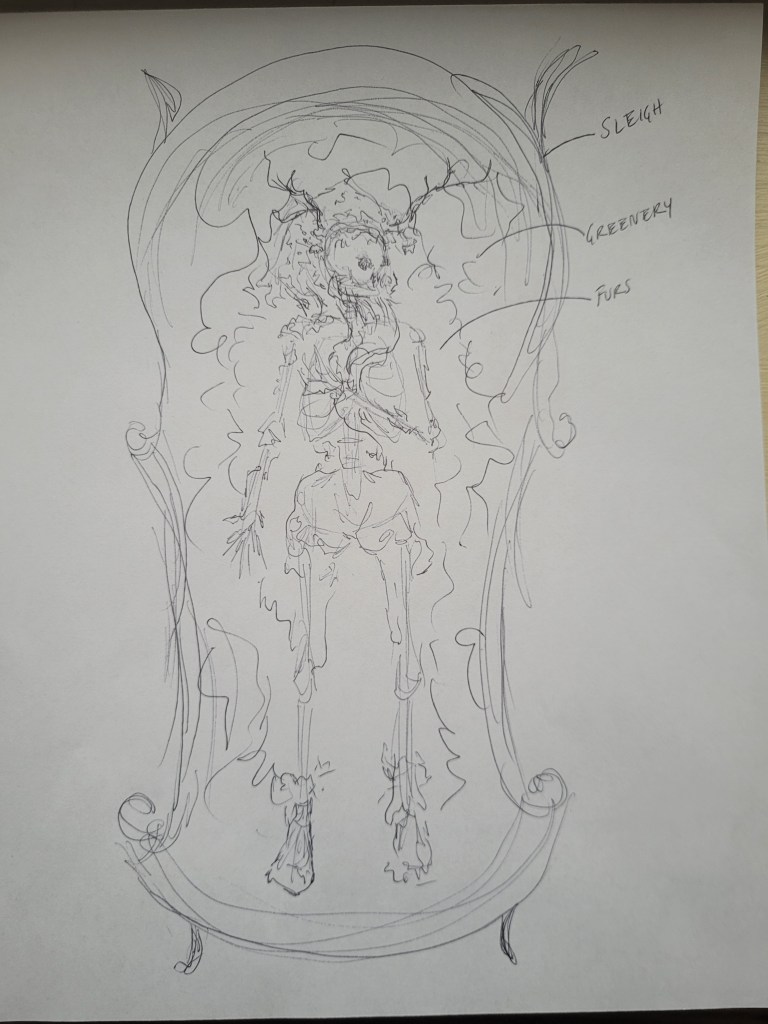

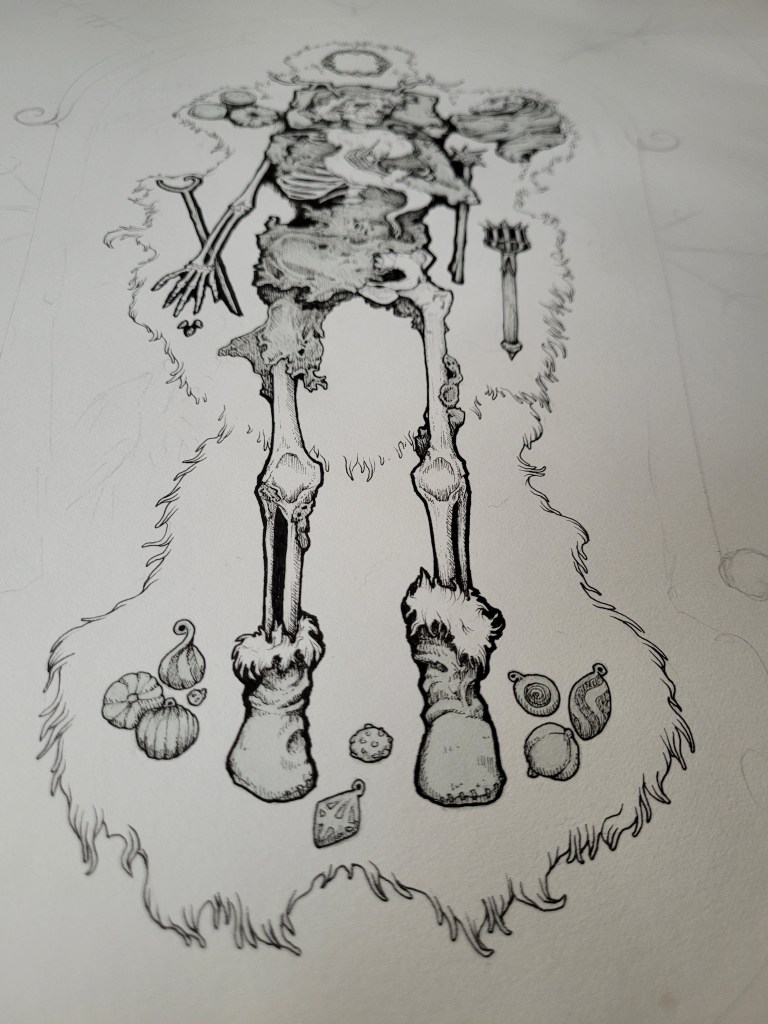

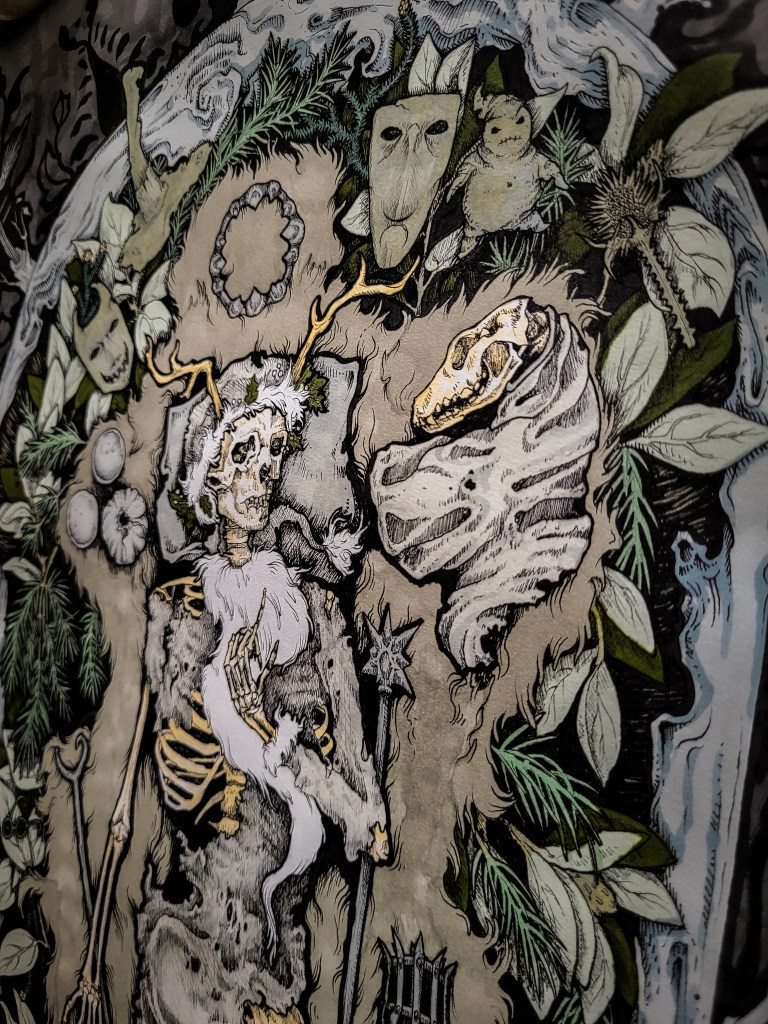

“The Pumpkin King” Pen and Ink, Isilee’s Markers 18″x24″

Done in a 800-1000 AD Scandinavian funeral style, each of the four major stave points representing a season.

I’m about to annoy a lot of people, to be a killjoy and perhaps to read too much into something that was only ever meant to be entertaining. But…I’m not sure I can help it, at least in part.

Growing up, when my family went to the movies, my father would pull into the Regal Cinemas parking lot and tell us to keep a series of questions in mind. Questions like: What was the worldview of the director, producer, and author of the screenplay? Did this story assume a moral imperative, and if so, what was it? What made the villain bad, and, if looked at from another perspective, could the villain then become the hero?

I HATED these questions, and would usually try begging, “Can we please, please just watch the movie?”

My father was unrelenting, and Caitlin and I would stalk into the theater, rolling our eyes with intensity. I remember thinking, If I ever have kids, which I WON’T, I’ll never make them do this. I will never be this judgmental and obnoxious.

When the credits finished rolling, and my father turned to us in expectation, I made myself willfully dumb, shrugging off the attempted lesson.

“I don’t know,” I’d say. “The point of a movie is to be entertaining and fun; I didn’t notice anything else.”

“You aren’t trying,” my father would say.

“Yes, I am,” I would lie, scrunching my shoulders up to my ears and scowling.

I didn’t want growing up to cost me anything. To participate in my father’s efforts, I would have to give up the easy thoughtlessness of childhood. I was too short-sighted and stubborn to see the appeal, to understand that, in exchange for my less-than-blissful ignorance, I could receive a clever, thinking mind. I would become less malleable and more adaptable at the same time.

These days, I appreciate the lessons that seeped in despite my many attempts to barricade them away. Maybe it was just the asking of the questions that mattered. Maybe it was watching my father answer them for us. Little by little, his influence trickled past my defenses like rainwater running downhill until a veritable lake of habit formed. It’s a gift, this Lake Paternalism, and one I can pull from at will.

I find myself irritating my own children with it. They plug their ears and shriek like banshees or cast baleful eyes in my direction, muttering about my movie-ruining ways. I feel a little bad about this; I really do. I know what it’s like. Even as an adult, when I watch a movie, I’m usually looking to disassociate from reality a little and relax. I’m not always interested in a lecture on philosophy. I don’t blame the girls for wrinkling their noses, and I try to leave most films alone, offering up only sounds of entertainment and some snacks. Every now and then, though, Lake Paternalism rises, and an obnoxious series of questions and answers comes flooding out of me.

I saved this one until after Christmas, because the last thing I want to do is throw an unwelcome wrench in someone’s December. I’m aware that to many, if not most, of my friends, The Nightmare Before Christmas is not only a temporary holiday classic, but a year-round favorite. Feel free to skip this post, or to skim over it and disagree entirely. I won’t blame you.

The Nightmare Before Christmas has made me feel vaguely unsettled for a long time, almost…itchy. I’ve tried to ignore it, but the itch only grew with every observance. It didn’t make sense on the surface.

My peers are in their 30s and 40s, and many of us are still purchasing t-shirts, Christmas ornaments, costumes, Halloween wreaths, tattoos, and wedding cake toppers of Jack and Sally. These characters have been elevated as a nationwide symbol of high romance for aging goths, the film itself cemented in place as an ‘Outcast’s Manifesto’ of sorts.

The claymation creatures are well done, and Danny Elfman’s musical score is an excellent blend of upbeat and melancholy tones. I’m usually a sucker for oddball characters and Tim Burton’s artistic flair.

In many ways, The Nightmare Before Christmas follows the trope of a misunderstood monster, akin to The Phantom of the Opera, The Creature From The Black Lagoon, King Kong, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Frankenstein. I think they resonated with me and so many others during adolescence because I too longed to be seen, loved, and to fit in, but felt somewhat out of place. I often felt ugly or foolish, and these monsters were more familiar to me than the maidens with their perfect curves who ran screaming in terror from the creature who only wanted to love them but didn’t know how.

For those who haven’t seen the film, the stage is primarily set in the fictional world of Halloween Town. Its citizens are made up of bizarre and conventionally unattractive beings who sing and dance and compliment one another on their strangeness. No one here is well-adjusted. Jack struggles with existential angst. Sally has a difficult home life. The Mayor suffers from anxiety. Dr. Finkelstein is lonely.

Despite its benevolent wrapper, I maintained that troublesome itch, the one that said all was not as it seemed. And now, the lake is flooding, and my children are threatening mutiny on its shores.

The citizens of Halloween Town are not simply quirky. They have little redeeming value when it comes to moral fiber, and while they have a Mayor, their true leader is Jack, the Pumpkin King. He makes and approves plans, gives orders, and is well-informed and well-liked. The current state of Halloween Town could be said to be attributed to him.

In the film’s opening scene, the population is fawning over Jack amid post-Halloween festivity. As the evening winds down and dawn approaches, he wanders with his dog, Zero, into the surrounding countryside. Even though he has had a significant hand in creating the life he leads, he feels a great void inside. He sings,

“There’s an empty place in my bones,

That calls out for something unknown,

The fame and praise come year after year,

Does nothing for these empty tears.”

These words resonate. The part of me that so often searches for more: more knowledge, more inspiration, more anything, perceives a mirror of sorts in Jack’s song. Public success and affirmation did not equal the ‘more’ he sought, and he seems trapped beneath the crown of the Pumpkin King. I think we have all felt trapped in relationships, jobs, and roles, claustrophobic under the expectations of both others and ourselves.

As Jack wanders, Sally (a sort of female Frankenstein’s monster) happens to overhear some of Jack’s song and she too, sees herself in its mirror. Unfortunately for Sally, she cannot see the vast difference between the two of them. Sally was created by Dr. Finkelstein as a romantic partner but must have disappointed him or resisted the role laid before her. The doctor calls her ‘treacherous,’ and holds her captive, a slave. On this evening, she has run away, but had to leave her arm behind. She has scanty choices available to her, and yet, the mantle of captive creation does not fully define her. She is generous and kind, managing to sustain herself by cultivating an internal ‘garden,’ attempting to grow into something strong enough attain freedom. Jack, however, has immense social power and privilege. His captivity is self-imposed, and at any point, he could cast it off. Yet, in a very human way, he would prefer to seek out the distraction of escapism over the toil required for real change. He desires something external to fill an internal void.

When Sally returns to the doctor for her arm, I do not think it is really for the arm. She reveals that she has run away more often than he knew, and yet she always returns. Women in situations of abuse frequently return to their abusers, unequipped for the world and without resources or support from their communities. They often long to be seen by their abusers, to be validated, even apologized to. Instead, the doctor focuses on the guilt that Sally ought to feel. He tells her that she ‘belongs’ to him, like a lamp or a carpet bag, and that her thoughts and feelings are merely a phase with which he must be patient until she gives in.

This, too, I find familiar. My ex-husband and the father of my children apologized to me once in a text, years after our divorce. I cried for an hour, and for a long time I had a screenshot of that apology saved on my phone. I never showed anyone else, but every now and then I would till the ground of my storage, pulling unnecessary weeds, and unearth this image, the harsh blue light glaring against my eyes, buried treasure revealed. It has since been deleted; I don’t need it anymore, but for a time, I clung to it.

Jack’s wandering led him to Christmas Town, and there he witnesses a new way of life, peering in windows and over rooftops. He sings,

“(I) never felt so good before…

I want it, oh, I want it

Oh, I want it for my own.”

He speaks to no one in Christmas Town but assumes that whatever qualities they possess cannot only be his, but that he can improve upon them once acquired. He is so good at being the Pumpkin King that he is certain he will be just as good at being the King of Christmas. This desire to claim ownership before seeking understanding would perhaps be acceptable if he were twelve years old. Selfishness is a part of youth; it must be, but Jack is presented as an immortal being, and his lack of awareness surrounding obtuse appropriation is unsettling to say the least.

Jack pilfers a heap of belongings from this new world and returns to Halloween Town, triumphant. He briefly tries to explain Christmas to his citizens before losing patience with them, presuming them to be too stupid to grasp what he has easily perceived. He takes advantage of their admiration and reverts to manipulation, deceiving them about the nature of ‘Sandy Claws’ to gain their enthusiasm and labor.

Jack then visits Dr. Finkelstein to borrow some equipment. He and the doctor seem to be on familiar terms, and Jack must be aware of Sally’s circumstances. He either finds Dr. Finkelstein’s behaviour acceptable or he’s uninterested in what does not benefit him.

Meanwhile, Sally runs away again by throwing herself out of a window and takes this time to deliver a thoughtful dinner basket to Jack. She has created a nice mental picture of who he might be, though it is likely anything would seem better than Dr. Finkelstein. She quickly runs off to the local graveyard, continuing to follow a pattern of abuse. It is extremely difficult to escape a flight response, even when approaching something perceived as positive. Short burst attempts at building social bridges are often made before retreating to analyze and observe. If these efforts are rewarded, they may become more frequent or of longer duration, but if punished, they may disappear altogether. Our hero here offers up a neutral response. He does not call out a thanks or attempt to pursue her. One could give him the benefit of the doubt. Maybe he understands her wounded animal nature. Move too quickly, and a feral being will not trust you or allow you to help it.

However, Jack’s next actions do not indicate that he thinks of Sally at all. He is far too busy launching into an anthem titled ‘Jack’s Obsession.’ He tries to unravel why and how Christmas has affected him so deeply. He doesn’t consider asking others from either town for their help. Instead, he delves inward again and again, and when this fails, Jack decides that Christmas must not be as deep or complicated as it has been made out to be. He has been trying too hard, because if the answers to his questions do not lie within himself, they must not exist at all. Instead of pursuing the truth about Christmas, he manufactures his own, singing,

“Why should they have all the fun?

It (Christmas) should belong to anyone.

Not anyone, in fact, but me…

I bet I could improve it too,

And that’s exactly what I’ll do.”

Jack enlists the Mayor’s aid and gathers the people of Halloween Town, assigning each of them a new job. The town’s original purpose is deviated to satisfy his personal desires. He calls for Lock, Shock, and Barrel, ‘Oogie’s Boys’ who live on the outskirts of town. The Mayor is clearly upset. He and the rest of the community dislike the boys. They have ‘taken things too far’ for lack of a better term, and have been shunned for it. Jack ignores the Mayor and flatters the boys, charging them the task of kidnapping ‘Sandy Claws.’ Jack tells them to treat him nicely, but they do not understand what that means, calling his judgement into question.

Sally is assigned a job that she is uninterested in accepting, and she tries to tell him of her misgivings four separate times. Jack dismisses her, resorting to that tried-and-true flattery and talking over her to get what he wants. When Sally dares to persist, he dismisses her physically, and the Mayor calls forward the next citizen in line.

As everyone attempts to cater to Jack’s delusion, he sings,

“I don’t believe what’s happening to me

My hopes, my dreams, my fantasies.”

Halloween Town is starting to look more like a cult and less like a community. Jack is the charismatic Great Leader. The town is isolated, its members sequestered save for an annual excursion controlled by…you guessed it, the Great Leader. Communication with those who might challenge the group’s beliefs is nonexistent. Language is transformed (we are not Halloween; we are Christmas) and thought reform begins. Critics within the group are quickly silenced and redirected.

When Sally labors to tailor Jack’s Santa suit, she tries once more to share her concerns.

“You don’t look like yourself, Jack. Not at all,” she says.

“Isn’t that wonderful! It couldn’t be more wonderful,” he replies.

“But you’re the Pumpkin King,” she says.

“Not anymore. And I feel so much better now,” he says.

“Jack, I know you think something’s missing, but…” Sally begins.

But Jack is fixated, having determined that this is the thing that will finally make him feel happy and whole, the town united in single-minded purpose. Even when the kidnapped Santa is delivered to him, the best individual to explain Christmas, Jack sends him away in a large black garbage bag with Lock, Shock, and Barrel. They will clearly not make good guardians, and Santa could easily die, but Jack’s personal narrative is worth more to him that anyone’s life.

As he’s dragged from town, Santa cries, “Haven’t you ever heard of peace on earth and goodwill toward men?”

The boys yell, “No!”

This scene is clearly meant to be funny. Santa is wholesome, but rather boring and helpless. The residents of Halloween Town are unique and intriguing. Peace and goodwill are portrayed in a trite, almost negative light, along with any semblance of normality. ‘Normal,’ it makes clear, is not good, a concept that has been adopted by outcasts and adolescents across the country. ‘Normie’ is an insult of the highest order, although when you look at the definition of the word normal, it includes:

“Serving to establish a standard.

Free from mental disorder; sane.

Free from infection, disease, or malformation.

Of natural occurrence.”

Somehow, it has been determined that these traits are negative ones, and their opposite is what ought to be sought if one is to be at all interesting. This is somewhat epitomized when Dr. Finkelstein places half of his brain into his latest companion creation, his consciousness existing in both a male and female body. He exclaims that it will be a joy to have ‘so much in common’ with someone at last. Unable to develop healthy connections with others, the doctor would rather wallow in dysfunction, in love with himself, than evolve. What will become of Sally now?

As Jack flies away in his coffin sleigh, Sally sings a lament. She is struggling to reconcile the reality of who Jack is with the dream of who he could have been. She sings that ‘it wasn’t meant to be,’ and seems to crumple inwardly, grieving the loss. In this backwards world, she is Quasimodo, the Phantom, and the Creature, ostracized and wounded for wanting only to love and be loved, her normality abnormal.

Jack flies above Earth, delivering frightening and occasionally deadly gifts to the public. His offerings are met with screams and cries to be left alone. He yells, “You’re welcome!” Jack cannot imagine a narrative in which he is not the hero. It is his Christmas, and therefore it must be a success. When searchlights and gunfire seek him out in the sky, he is still convinced that he is being celebrated, and it is only when he is blasted to earth that the truth begins to seep in.

He mows through the classic steps common among narcissists when a personal mistake is made.

1. The crush and disappointment of failure: “What have I done…How could I have been so blind…Spoiled all.”

2. Dramatic shame that must be witnessed by others sooner or later: “Find a cave to hide in, in a million years they’ll find me, only dust and a plaque, that reads ‘Here Lies Poor Old Jack.'”

3. Martyrdom and turning the disappointment away from self and onto external events: “Nobody really understood…all I ever wanted was to bring them something great. Why does nothing ever turn out like it should.”

4. Re-writing the narrative: “What the heck, I went and did my best…I really tasted something swell…I even touched the sky…I left some stories they can tell.”

5. The rebuilding of character to avoid negative feelings: “I am the Pumpkin King, hahaha…I just can’t wait until next Halloween.”

Meanwhile in Halloween Town, Santa has been taken by Lock, Shock, and Barrel to their leader, Oogie Boogie. Sally attempts to rescue Santa and fails. Jack sweeps in with agility and bravado to save Santa and Sally from a situation he himself created. He offers a mild apology to Santa, and he is once again the champion of the story, his transgressions forgotten. A Great Leader knows that if one is confident and loud enough, their narrative is seldom questioned.

The film closes with Jack telling Sally that they are ‘simply meant to be.’ She forgets her song of lament, swayed by the attention she has clearly been craving and the drama of his rescue. The film closes with the two of them sharing a kiss in the moonlight, but Jack’s story carries on in James and the Giant Peach.

Lost once more in escapism, he is Captain Jack, the Pirate Lord. His ship sits at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean with a host of undead creatures. He has either dragged his community with him or found a new crew to govern. They torture Mr. Centipede and try to kill the rest of the characters, Jack’s Christmas lesson unheeded and Sally nowhere to be found.

To conclude, what I like least about The Nightmare Before Christmas is the way it feeds emotional junk food to the part of us that seeks a sense of belonging. The way it tells us that we can be selfish, cruel, and unstable and expect to receive generosity and affection in return. It teaches us to settle for our dysfunctions, and to expect our loved ones to not only put up with them, but to embrace them or be left behind.

I do not suggest that these problems are solely the product of a single film. The Nightmare Before Christmas is part of a much larger and many-faceted social, economic, and political movement that has shaped generations of Americans. It is entertainment for the cult of the individual, a widespread, cancerous, and almost invisible thing. We think of cults, and we think of bizarre religious groups and Kool-Aid deaths. We think of cults as ‘other.’ “That is not me, not my friends. I would never fall for that or be part of such a sham,” we tell ourselves.

And yet, here we are, consuming what we have been spoon fed and demanding more, feeding our starving hearts bowlfuls of Capitalism Crunch washed down with cans of Diet Morality.

I write these words, and Lake Paternalism recedes, exposing something soft. I didn’t come here to mock Nightmare lovers or to say that everyone who has ever enjoyed the film is a cult member. We’re all in this together; we all have amusements that we don’t look at too closely. I was obsessed with Star Trek: The Original Series and Time Bandits as a child. I’m sure there’s a lot to unpack there between Captain Kirk’s constant philandering and Kevin’s parents exploding after touching some toaster-oven Evil.

Perhaps you were an anxiety-riddled preteen on a middle school field trip, clutching your Sally backpack for dear life. You noticed a kid across the aisle wearing a hoodie that sported Jack and Zero frolicking through some spindly trees. All of a sudden, you were less alone and less anxious. Maybe you worked up the courage to say, “I like your hoodie,” and smile. Maybe you made a friend. The Nightmare Before Christmas did for outcast kids what sports teams did for Jocks. You both root for Virginia Tech and give each other a bro nod – sweet.

Maybe you’re a high school teacher, and your heinous, themed dress created the connection a student needed to truly hear your words of encouragement. Their heart and ears would have remained locked away without the key of something shared. Maybe your nostalgia re-directed a life, and you didn’t even know it.

Were you an impossibly thin boy who hated Halloween and its muscle-bound superheroes? Nothing fit and what did was awkwardly padded and seemed like a ludicrous mockery of your reality. Along came Jack with his long limbs and snazzy stripes, offering relief.

Were you a girl who played with Barbies, watched a seemingly endless parade of Disney princesses, and felt horribly inadequate every time you looked in the mirror? Then you found Sally. With her somewhat lumpy body, yarn hair, and unconventional face, she looked almost like a young Yzma from The Emperor’s New Groove. And yet, she was the female lead, paired up with the Pumpkin King of all people.

Maybe The Nightmare Before Christmas saved your life, and for that, I cannot dismiss its value. All I can do is gently prompt you, now that we are older, to find better heroes. Perhaps we’ve outgrown the Jacks and Sallys of our youth. I’m reminded of these lyrics from The Beatles:

“Though I know I’ll never lose affection

For people and things that went before

I know I’ll often stop and think about them

In my life I love you more.”

Maybe we need to love ourselves enough to create or become what we needed but couldn’t find, all those years ago, both for ourselves and the next generation.