It’s one of the first things we ask when we meet someone new after exchanging names. Even if we don’t feel that our career defines us, if we reject that box because we resent it or we don’t like what it might say about our choices, we are defined by it socially. It’s what we’ll spend most of our lives doing, and therefore we’re enmeshed with this role more than almost any other.

Growing up, I imagined myself with a variety of vocations. Astronaut, air force pilot, racehorse jockey, artist, swamp hermit (I watched Girl of the Limberlost too many times), naturalist, archaeologist, the list goes on. I wanted something thrilling, something that piqued my interest. I wanted a clear goal and sense of purpose, to be the heroine in my own life. I don’t think that changed much as I got older, but it did become buried beneath a heavy layer of practicality. I got married. I had kids and became a mom, and then I became a single mom. Most of my dreams seemed difficult to attain, and I reined myself in. Conversations with friends and strangers let me know that others shared my feelings. OR they got what they wanted, and they realized it wasn’t what they thought it was going to be. It was more obligation, less whimsy.

I see versions of a particular meme on my socials every year. There is normally a nature photo in the background, or it’s surrounded by a border of something ‘magickal.’ It goes something like this:

“The world is full of blubbery caterpillars that transform into velvet moths and more stars than we can count in a lifetime and red salamanders that look like jewels against the black earth but go brown against your skin because our very essence drains theirs. It’s full of cicadas that live underground longer than our domestic dogs are alive, only to emerge and grow wings for a summer like last-minute angels before they fade away. It’s full of thunderstorms that rattle my chest and mountain peaks that sweep up and away to oceans whose depths hide an alien planet. Why do I need to be a lawyer or an accountant or the manager of a Honda dealership? Why can’t I spend my life drinking this in and reveling in the mysteries around me day in and day out? I long for a life my nation has labelled taboo. We move from school to career to old age in one seamless line. I’m longing to break free from this unnatural, soul-killing routine.”

The answer to that is: we aren’t dogs or salamanders or caterpillars, and even if we were, we wouldn’t spend our time reveling; we’d spend it sustaining and surviving. An amoeba, for all intents and purposes, a limbless, brainless blob, will spend its time engulfing bacteria, producing more of itself every so often, and hiding out when bacteria is so scarce that it begins to die. When this happens, it will stay in a sphere shape, its exterior often hardening while it divides over and over internally. Then it explodes, releasing all those new ‘daughters’ to live the same lives. If the amoeba stays in its sphere and doesn’t reproduce and explode, it will usually die. Feed, divide, mature, explode, die.

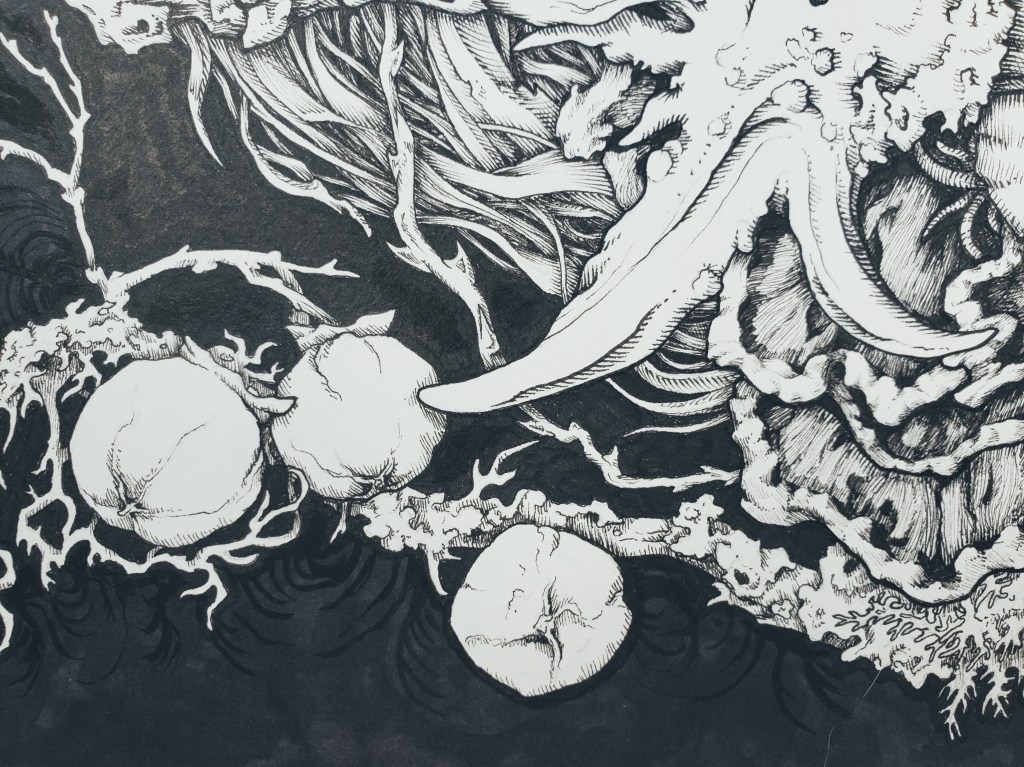

An amoeba engulfing bacteria by Science Photo Library.

All living things have certain requirements within their design, and those requirements increase alongside complexity and intelligence. An inherent part of the human design is the absolute need for purpose beyond consuming and reproducing and dying. Without purpose, no matter how pleasant and carefree our lives become, we fade into depression or go mad or some combination of the two.

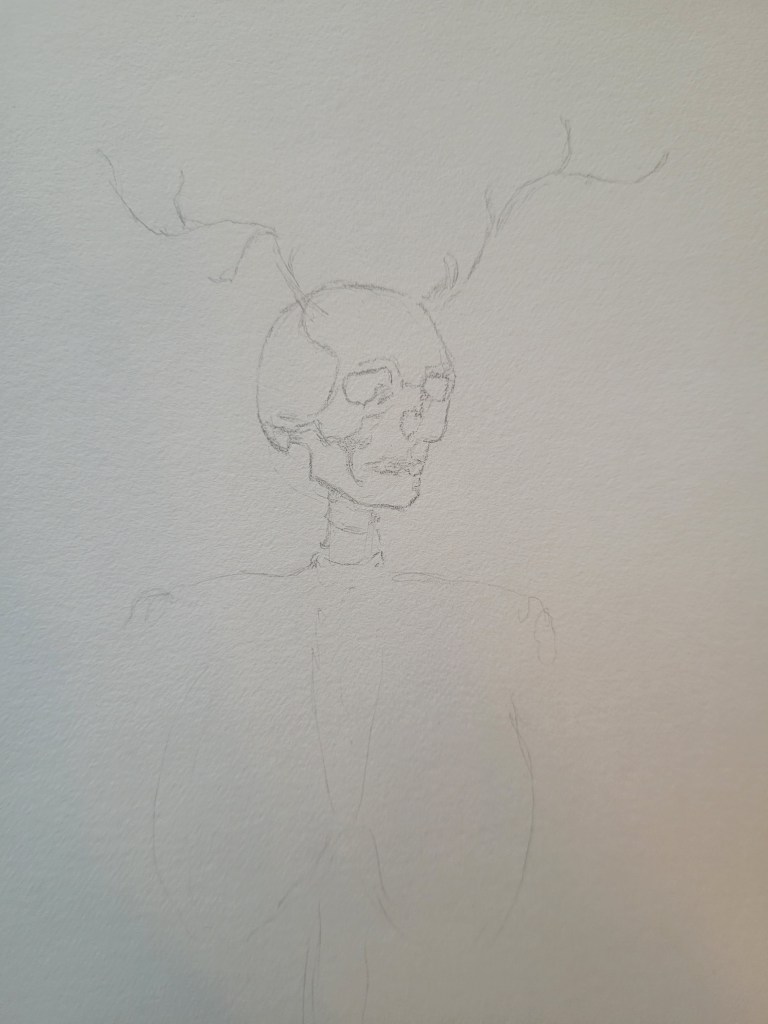

For me, purpose has come in so many forms, but when it comes to work, the job that pleases me best is this one. (I don’t count being a mom. Not because it isn’t labor intensive, but because I AM a mom. I can’t abandon being a mother and move on to another career. It’s forever.) Or, at least I hope it’s going to be this one. I’m putting it out there. We’ll see what happens. I used to think my art wasn’t about gifting anything to anyone, and maybe that’s the way it used to be, all selfish and vain and oh so personal. The year I went through my divorce I didn’t draw or write anything at all. I couldn’t even hover a pen over a page without crying. There was too much of me, and no room for it. It felt like drowning in myself, and the only thing keeping me afloat was silence. I withdrew, and I think I’ll always regret it. The only time my youngest daughter heard me cry was in the bathroom with the water running while I sobbed in the floor. She sat outside and didn’t know what to do, and I wasn’t at all aware of her struggle until years later when she told me. I think my eldest learned to be stoic and isolated from me because it’s the example I set. Now I’m trying to undo all of that silence, and maybe that’s most of what the book I’m writing is about. I’m starting things over again; I’m trying to be a better mother.

Me at 19, pregnant with my oldest, who is now pretty much the same age I was in this photo.

I feel lucky pretty lucky when it comes to career stress. My parents have had a lot of money, and they’ve had no money. Their empire has risen and fallen and risen again and fallen again. And the world didn’t stop. It didn’t kill them. You can start over no matter where you are or how old you are, and that lends itself to reinvention and opportunity. Our careers and routines should be fulfilling, not ‘soul killing’. They should be as delicious as looking up at the night sky and glimpsing the milky way. They should harmonize with our souls. I don’t mean twenty four hours a day; that kind of joy is unattainable, and without the contrast of boredom and irritation, it would become meaningless. Life is peaks and valleys, and that’s a good thing, but there should be a lot more peaks than there are valleys. If there aren’t, we’re doing life wrong.

The peak to valley ratio isn’t about chasing euphoria or thrills all day in a sort of manic death dance. It’s about living with purpose, so the peaks come to us and not the other way around. We don’t have to be fire fighters or opera singers or surgeons to attain purpose, though if you are, good on you. Our interests and the opportunities available to us are going to be varied. You might work as a fuel attendant all your life, but that doesn’t make your work purposeless unless you allow it to be. This whole thing is more about mindset and the way you do your job than it is about the job itself.

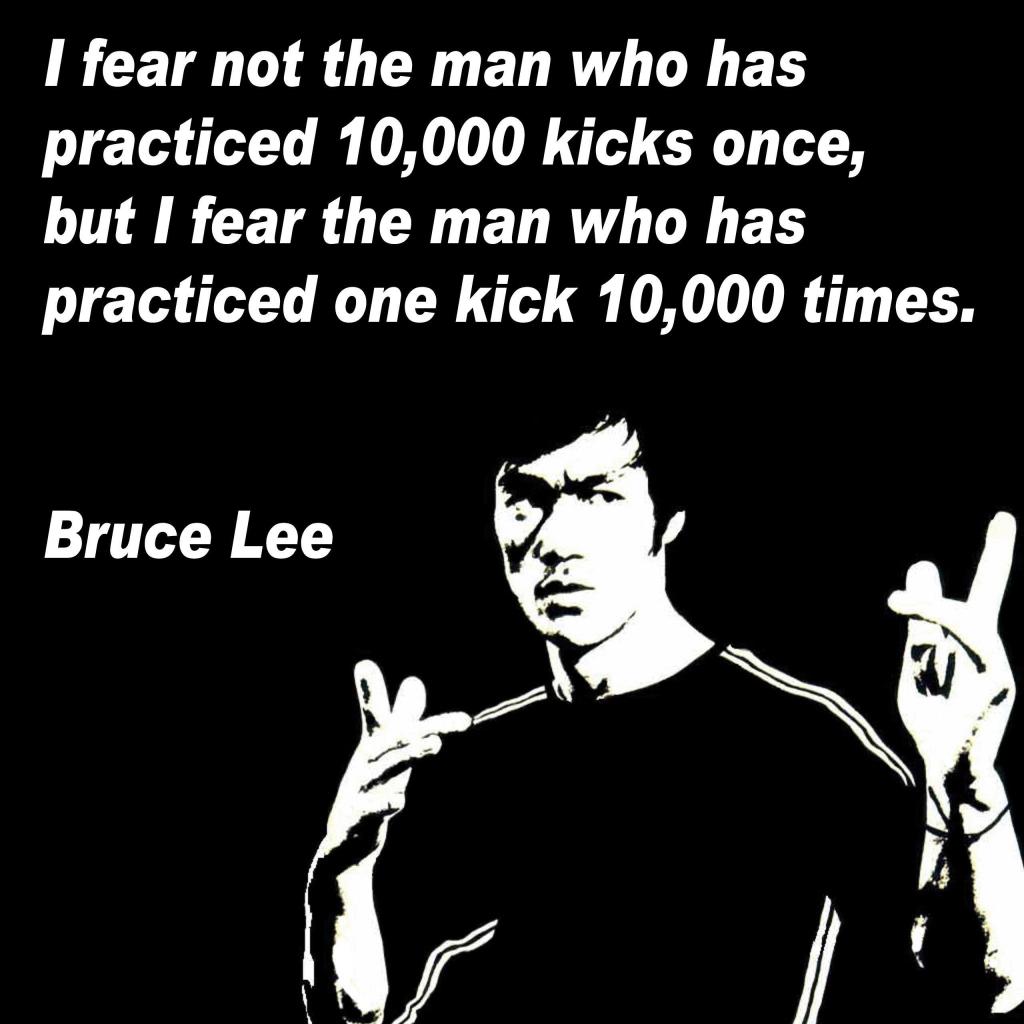

There is a scene from the television series Marco Polo where a character named One Hundred Eyes is instructing Polo, and it’s stuck with me. He says,

“If you one day you make it back to the West, what will you tell men of this strange word, “Kung Fu?” Will you tell them that it means to fight? Or will you say, like a monk from Shaolin, to summon the spirit of the crane and the tiger? Kung Fu. It means, “supreme skill from hard work.” A great poet has reached Kung Fu. The painter, the calligrapher, they can be said to have Kung Fu. Even the cook, the one who sweeps steps, or a masterful servant, can have Kung Fu. Practice. Preparation. Endless repetition. Until your mind is weary, and your bones ache. Until you’re too tired to sweat. Too wasted to breathe. That is the way, the only way one acquires Kung Fu.”

Strive. Be present. Exert Effort. Be persistent. If you are a salesclerk, be the best salesclerk. If you are a guide in a National Park, be the best guide. Mediocrity is the death of happiness.

Opening the door for someone and gifting them a genuine smile can make a morning that would otherwise have sent an entire day spiraling downward into something with grand potential. If you’re swiping and bagging in the checkout line, do it with the grace of a dancer. Find something good about your customer or co-worker and tell them what it is. When you pass away, people don’t tend to remember how much money you made or if you got as much vacation time as Bob. They’ll remember if you lived your days with purpose or not. The only person who can make you small or bitter or insignificant is you.

In April of 2022, I got a call from my sister, Caitlin, telling me that our father had been in a car accident. He’d been taken to VCU’s Critical Care building with a head injury. I spent the day on the phone with my siblings and mother, twiddling my thumbs and waiting for news. That’s the downside of living in a different state; you can’t pop over during a crisis because travel requires planning.

I got permission from the schools to pull both kids out for the rest of the week. I coordinated with Edwin and checked in with work. The girls and I left the next day. We didn’t realize that minors under sixteen are not allowed to visit the ICU. I didn’t know that children who have dying mothers and fathers and grandparents are not allowed to say goodbye. They must sit in the waiting room, peering down the hall every time the corridor door swings open, willing their goodbyes along fluorescent pathways. There were a lot of things I didn’t know then.

The girls stayed with my brother Neil, and I ventured on to the hospital to meet my mother. All told, my father had several brain bleeds, multiple skull fractures, and a fractured and broken right orbital socket that was impinging upon his optic nerve and severing the flow of blood to his right eye. His neck and low back were fractured in multiple places, his right lung was collapsed, his right shoulder was dislocated, most of the ribs on his right side were fractured or broken, his pelvis had multiple fractures, his right patella was cracked, right femur fractured, and right foot fractured in multiple places.

He arrived without identification and was given the name XE Cento as his ‘John Doe.’ They estimated his age to be between 64 and 65 based upon appearance and vitals. He would be 75 in four months. My father had been a strong and healthy man.

My mother holding my father’s hand.

He slept for almost a month. We watched his facial expressions and the monitors with intensity. The numbers all meant something, and it was all we had to tell us whether things were getting better or worse. He stopped responding to commands and painful stimulus. AFIB was in and out. His blood pressure was good and bad. The swelling in his brain waxed and waned. Procedures came and went. The room smelled like old blood and plastic. Wires, tubes, and drains flowed from him like something from Star Trek.

‘We are the Borg. You will be assimilated. Your uniqueness will be added to our collective. Resistance is futile,” I could hear him joking in my head. Star Trek had been ‘our show.’

I had a playlist on my phone called, “My Dad’s In a Coma.” It had songs like ‘Golden Slumbers’ by The Beatles, ‘Call It Dreaming’ by Iron and Wine, ‘In The Arms Of Sleep’ by The Smashing Pumpkins, ‘All I Have To Do Is Dream’ by The Everly Brothers, and ‘Sound-A-Sleep’ by Blondie on it. I’m not sure why I did that.

I stared at his eyelids, one of them purple, bloody, and unable to close over an eye that looked like an over-sized, gelatin-filled bouncy ball. and the other as normal as it had ever been.

‘Open your eyes, open your eyes, open your eyes,’ played on a loop in my head.

I sang the songs he used to sing to me when I was a child, and I didn’t want to get out of bed. He would leap up and down on my mattress, shouting the words to ‘Morning Has Broken’ by Cat Stevens and ‘Good Morning’ from Singing In The Rain. As a child, I’d bounce and shriek like mad. It was my favorite way to wake up. He didn’t wake up.

His nails got longer and cracked at the edges. His hands and feet swelled from the saline and medication drips. His cauliflower ear went back to its normal shape. His right eye slowly descended back into its socket, and I stopped worrying that it would rot and run down his cheek like awful jam. I read The Fellowship of The Ring to him, nattering on about how he was like Frodo right now, and we were his Company. Neil, the oldest of us, would be Pippin: charming, smoking his pipe-weed, and somehow able to make every nurse laugh and feel at ease in spite of the gravity of the situation and the fact that it was tearing him apart like Saruman’s Palantir stone. Laura, next in line, would be Legolas: elven, unyielding, her clear and perfect voice filling up the hospital room. I suppose I would come along then, but it’s hard to see oneself, and I was too tired to try. Caitlin would be Boromir: full of a love of home and family and so devastated by impending loss that she had to stay away.

My mother was Sam, of course, never leaving our father’s side and urging him on. She put tea tree oil on his toenails ‘so they would look nice for the beach.’ She moisturized his face and legs. She told him how handsome he looked and how much she missed him. She prayed for him and held his hand and watched everyone who entered the room like a hawk with rabies (I don’t even know if hawks can get rabies, but if they can, I’m sure that was what it’d look like).

We watched the patients in the halls. Some of them were walking assisted, others were sitting in wheelchairs, and yet others lay on gurneys with their heads moving back and forth so they could see their surroundings. We would have given anything to have my father be one of them, any of them.

We did our best to stay upbeat. We played classical music and danced. We made faces out of the windows. We threw bits of band-aid wrapper at each other. We talked about memories and things we would do differently when…if…my dad woke up. We waved sad, limp hospital lettuce at each other. We laughed so hard that we couldn’t breathe. We also cried. We cried a lot.

Manic moments in the hospital room.

Edwin’s own father had passed away several months before the accident. They’d had a complicated relationship, and in true-to-form fashion, his death was equally complicated. There wasn’t a funeral. It took months just to receive a cause of death. Surprises came and went. I think Edwin truly wanted to be there for me. He would pat my back in a sort of absent-minded way, and he suffered my frequent absences with patience. He asked me how I was once. I only remember it because the question startled me. For the most part, my husband was an ill-tempered ghost. The whole world irritated him. He barely looked at me. He wandered off in the middle of conversations, staring straight ahead as if in a dream. The man who had joyfully frolicked across a bog only a handful of months earlier seemed like something from a dream. This isn’t fair, I remember thinking. Why can’t we take turns with our tragedies?

Life isn’t always interested in fairness. In some strange and inexplicable way, the unfairness of it all was sort of acceptable. Maybe Edwin couldn’t talk to me about his feelings, and I couldn’t cry in front of him. Maybe he didn’t want to touch me, or even kiss me, and maybe I couldn’t provide a warm, clean haven of a home. but we had something else. The sadness in me saw the sadness in him. We grieved near each other, two moons orbiting around the same lonely planet.

And then my father woke up. It wasn’t all at once, like in a movie. It happened on a weekday, so I was back home in Pennsylvania. Neil sent excited messages and called to share the details, painting a picture for me. One eye opened, and then the other. It was only for a moment or two at first, and then longer. He would track the people in the room in a sort of fuzzy way. He couldn’t speak. He couldn’t move more than a little. But that didn’t matter; he was awake.

Taking a break outside with the kids.

It has now been almost two years since the accident. My father has thrown food at me – a sort of pureed blend of pork, peas, and rice that smelled of feet. He has whispered a desire to give up, to go insane, to die. He has poured his own urine on his head like a terrible baptism. He has screamed in pain. He has forgotten the words for common-place items. His hands have been like claws and his muscles have atrophied in extreme ways. He has called my mother a creepy old woman, and she has run from the room weeping out of exhaustion, loss, and hurt. He has looked at me the way he looks at his nurses, a kind stranger in a strange land. He has told me that I am not his daughter. He has called me on the phone to ask who he is. He doesn’t want to know his name, he wants to know who he is supposed to be, and what sort of purpose his existence fulfills (don’t we all). Somehow, he has believed that I’ll have the answer. He has cried with his mouth wide open, great sobs shaking his body. He has been trapped in the past, 30 years ago, ten years ago, five years ago. He has ignored the girls when they were able to visit, refusing to look at them and waving them away. He has perseverated on his trach, his feeding tub, his catheter, his blankets and socks and bed pad and anything else in reach. He has confused utensils, trying to use a spoon as a straw and a straw as a toothbrush. He has talked in loops for twenty minutes at a time, saying things like, “I want fish food,” “I want to trade animal flesh for some man flesh,” and “How do we know if new things are new?” He has hallucinated a monkey, a small white dog, a kitten, snakes, insects, and family members. He has had no desire to share his food, drinks, or blankets with my mother, whom he once shared everything with. He has talked over and interrupted everyone. He has believed himself to be the next President of the United States. Over and over, he has read aloud the sign that states in large, easy letters,

“Your name is Gordon Frantzich.

You were in an accident.

They are ok.”

Sometimes when he has read it, tears have rolled down his cheeks in steady waves. Sometimes the tears have been for what he has lost. Sometimes they are out of relief that he didn’t hurt anyone. This has made me angry.

***

He was driving sixty miles per hour, the speed limit, when Anna Chavez-Maples drove through a stop sign at a major intersection. She was going fifty miles per hour, speeding on her own road, when she hit him. The officer who arrived on the scene asked what happened after my father was taken away, and she replied,

“I didn’t have my morning coffee.”

Several days later she put up a Facebook post. I know, because every member of my family seemed to be scanning her social media as though it would somehow make everything more clear, more real, or maybe we simply hoped that she would display remorse and set our angry souls to rest. She said she was grateful for her safety and that of her infant daughter, who had been in the back seat. She was glad to be home, unharmed, with family. She did not mention my father or even that anyone else had been involved. She did not mention that the accident had been her fault. She has never reached out to ask about him or to apologize for the agony my family has endured. This was not her first reckless driving incident. We have mutual friends.

Sometimes I want to send her a letter. Sometimes I want to contact the school she works at, and warn them that if she does not have her morning coffee, she might hurt someone. I don’t do these things. Mostly, I hope that she takes her time now. I hope she is a good mother, wife, friend, teacher. I hope she offers the world more these days because she feels the gravity of life, and that she knows what she stole.

My parents were not like most parents. They really and truly loved each other, and not in that way that comes from being dependent upon one another or from having lived together for a long time. It was that ‘in love’ love. They held hands. They played badminton in the back field in their bathrobes. They went away for weekends to romantic cabins. They lived in a one-room studio home in the barn they had renovated. They read out loud to each other. They listened to operas and cried. They looked at each other with mushy doe-eyes. Not that they were perfect, of course. My mother could sigh and he could groan and they could both roll their eyes and snap at one another. But my parents were absolutely bonkers about each other all the same.

My father had just announced his retirement. He would only be working another six weeks, he said, and they would finally get to enjoy the time they’d been waiting their whole lives for. They talked about selling everything to live on a sailboat while they still could, roving the Chesapeake Bay once more. Or staying on the farm and planting an orchard. They were full of dreams.

Before the accident.

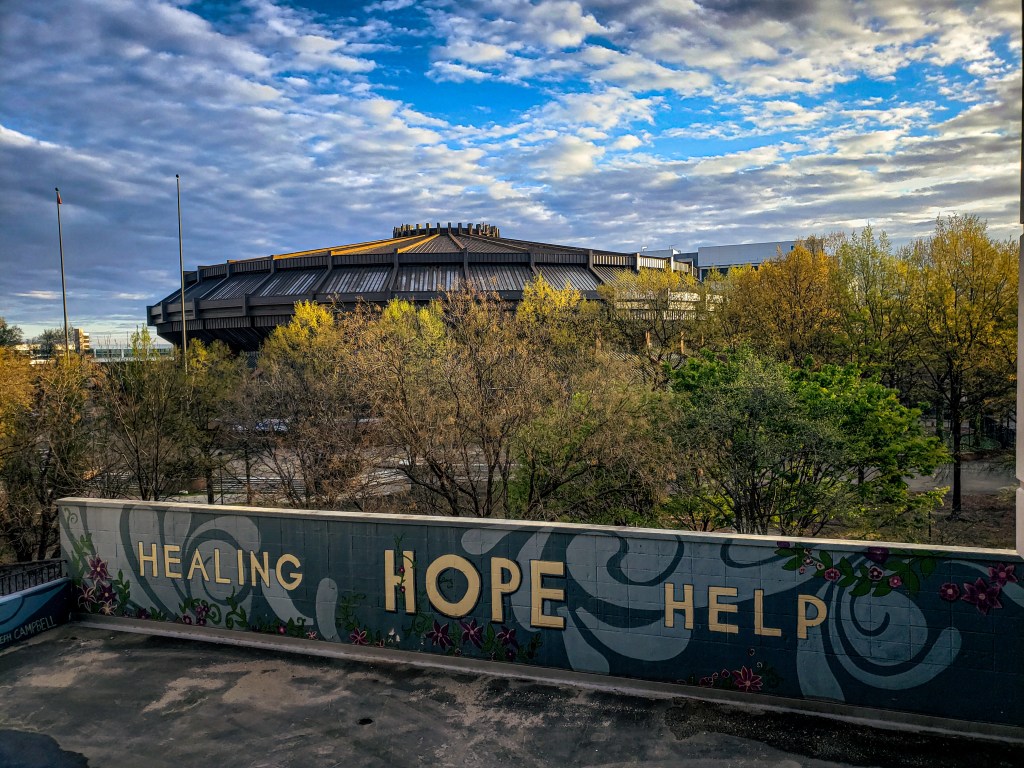

Initially, VCU provided my mother with a small but serviceable hotel room down the street from the hospital. A few days a week, students from their campus made dinner, and from her door you could see a mural with the words, ‘Healing, Hope, Help’ writ large. My mother joked that the people in neighboring rooms might think her a madwoman, because she had screamed, cried harder than she had ever cried in her life, flung herself about in a rage, and laughed uproariously all in a ten-hour span. I thought each of these rooms had likely seen similar fits. They were capsules of grief.

From there, she moved to a tiny red house owned by a friend of a friend of my grandmother’s. We called it The Princess Pagoda. The woman who owned it had decorated it with swaths of exotic fabric in a riot of colors. There were stained glass windows featuring doves and sun rays and green grass. There was a lovely little shower and soaking tub. We shared a bottle of wine in the garden there, and wished it was a vacation.

A dove sat on a nest outside the kitchen window, her babies stowed away under her wings. My mother dried her hair and put on her makeup and cried while ‘their song’ wafted from the shuffled Pandora station. We walked the downtown area and gazed at the water and Victorian architecture and the pig statues that stood on each block. Later, we discovered that one had to become a contortionist to wash one’s hair in the little tub because the shower head was only decorative, and the whole place was infested with brown recluse spiders.

It was on to another hotel, an even more temporary affair. The price was not cost-effective.

Trying some different smells to encourage cognition and memory.

Then a motel that smelled of fish, immigrant spices, and marijuana smoke. We cooked salmon on a hot plate and ate olives at a table just big enough for two chairs. My mother learned where to avoid once night fell and found a little stretch of beach nearby where we had a seaweed fight with the girls and threw a frisbee back and forth. There was a YMCA nearby, and my mother tried to establish a routine, attending water classes. I think this was more to wear herself out physically so she could sleep at night than anything else.

Her next-door neighbors woke her up at all hours screaming. She learned new and creative curses. We rode the elevator with those neighbors, a couple with a young boy holding a drumstick ice cream cone. His mother told him it looked like a penis and his father knocked it out of his hand and onto the ground.

“Fuck you,” the child yelled, and snatched his ice cream up like it was the most normal thing in the world.

My Mother has no ability to mask her expressions. A rapid play of horror, shock, interest, anger, and then the vapid, friendly smile she fell back on in situations of stress danced across her face like a robot short-circuiting.

Another elevator companion wore plastic hospital booties over her adidas slides, and two pairs of socks were tucked over her sweatpants by degrees. A hood was cinched tightly over her face, and her hands sported rubber garden gloves. Three surgical masks were layered over her mouth and nose, and a pair of wide goggle glasses hid her eyes. She dragged a suitcase behind her with each zipper tab swathed in saran wrap.

A knobby-jointed woman lived in a van outside, and two men came to visit her regularly. Most of her teeth were missing. The women in the lobby were delightful, loud, and eager huggers. They knew my mother by name and asked after my father. When it was time to move on again, they were sad to see her go.

Home didn’t exist for my mother anymore. Only my father existed, day in and day out. She made his meals, advocated for him when she needed to, which was a lot, and made decisions she never thought she’d have to make alone.

***

Four months and many moves after the accident, he was in The Laurels, an assisted living and rehabilitation center. My sister-in-law Mariah works there, and it was only seven minutes from their home, so my mother could move in with them.

On this particular day, I had come for a visit, and my mother left to run errands. My father slept on and off while I worked in the chair beside his bed. We talked when he wanted to. Some of it made sense and some of it didn’t. When his diaper needed changing, I called for a nurse. By the time she arrived, his clothes were wet, and by the time she had his diaper off, she realized she was out of trash bags. I had one in my bag for her. This was old hat by now. The bed was also wet, so I helped her lift my father and remove the soiled linens. She discovered that she was also out of replacements, and those I didn’t have. She stood there, unsure of what to do next.

“You can go and find some. I’ll stay with him,” I said.

“Are you sure?” she asked.

“I’m sure.”

She looked relieved. They were understaffed and over-worked.

My father lay on his side, arms and legs beyond small, the skin bunched at the elbows and armpits. His grey, non-slip socks were rumpled around his ankles and backwards. The adult diaper he wore hung wrinkled and loose on his emaciated frame. The navy-blue mattress beneath him had a stain in the middle. It wasn’t from today. It was months’ worth of stains in jagged circles, a tie-dye of brown rings, radiating outward in a melted sunburst from dark to light. Some other human being had lain here before him, pissing and shitting and vomiting. It reeked. My father tucked his legs in a little, his arms folded over his abdomen. He wanted to curl tighter, but he was too tired, his breath a series of sighs. His eyes were sad and confused and beyond humiliation.

“I’m cold,” he said quietly.

I sat on the edge of his putrid nest and put my arms around him, rubbing his back gently. He didn’t know me. All he knew was that his life was not what it should be. I loved him and missed him, my bog body of a father. The year had blended for me, coming full circle. Those things in their glass boxes at Ireland’s Museum of Archaeology were no longer alien. They were lodged in my heart. They, like my father, were once here in a glorious fullness of being. My father, the academic outdoorsman, who devoured books and could more easily and happily discuss quantum physics and world religion than he could the weather. The one who could run for miles only to leap into the arms of a tree for a round of pull ups at seventy-four years old. The one his grandchildren called ‘Exalted Grandfather’ and ‘Slash, the Warrior Cat.’ The one who wanted to live like old Caleb from the book of Joshua, who asked for the mountain of giants while younger men sought gentle valleys.

A patient across the hall yelled, “I like my coffee like I like my women: bold, black, full-bodied! Wait staff! Wait staff! I demand raspberry sorbet! I want it on my bedside table! Reset! Reactivate!” The moment was viscerally real and cartoonishly ludicrous all at once.

***

A month later, my father sat in his wheelchair eating a slab of pork and a side salad for lunch. He used to avoid pork, but now he hacks away at whatever lies before him, stuffing large portions into his mouth.

“This has a savage amount of fat,” he said finally, looking dismayed. “And this salad has iceberg lettuce. How did it become such a taste? It’s awful. It never truly became anything of value. Its life has no meaning at all.”

One of his doctors knocked and entered, doing his rounds. He asked my father for our names in a sort of memory and conversation exercise. My father pointed to me.

“This is Savage Fat,” he said. “I’m Iceberg Lettuce.”

I almost spit out my water, laughing. His doctor did not understand the joke.

Looking back, I found the whole thing less funny, and wondered if my father truly felt like his life had no meaning at all. I took to telling him that he was not at all like iceberg lettuce, and he would smile and say,

“Thank you. That means a lot to me.”

***

I should mention that the blue mattress was removed from his room, brown fluid pouring from its seams as it went. Mariah made sure a brand new one found its way there. This was not her fault. Everyone was doing the best they could. The janitors, CNAs, nurses, nutritionists, therapists, doctors – they all did their best, and their best was excellent. None of these places are capable of being perfect. You can’t expect them to be.

If you or a loved one is ever in need of their services, you won’t be perfect either. You have to be present and on top of medications, diet, diaper changes, and schedule. The system will not do it all for you. I know you’re probably tired and overwhelmed but do it anyway. My five foot two inches tall, sixty-nine-year-old mother did. Most of the time, she caught more flies with honey, but sometimes she had to be a ‘lioness’ to quote my father.

They are both home in their one-room barn now. He can shuffle unassisted across level surfaces. He can manage most of his own hygienic care. He knows who I am but not always how old I am or where I live or who I’m married to. He is more loving than he has ever been, and he cries easily. His impulse control is limited, which can be both frustrating and humorous. He prays for healing, especially for his mind and his blind right eye. Sometimes he puts in the work and sometimes he wallows so deeply in self-pity that he refuses to leave to couch. He knows he is different than he was, and he worries that what he can contribute to the family, and especially to my mother, is not enough. He tells the same stories over and over with great intensity. He can tell me about Meso-America, but he can’t remember the password to his laptop. He can give a whole sermon on Greek and marriage but can’t problem-solve his way through current issues.

He’s spoken of a desire to run out of the house and go to the ocean to swim forever with my mother, the woman he loves. He’s told my mother to abandon him or to take him out to the field to shoot him like a pet that can no longer lead a good life. He has learned to hug again but will never drive again. He has said that his mind is a dangerous place. If he doesn’t know what he’s looking for when he goes inward, he can become lost, and he doesn’t want to be lost in a bad place full of holes.

My parents have a court hearing coming up in an attempt to achieve some financial compensation on a variety of fronts. My father told me,

“We’ll go, but I’m not prepared. I don’t know what to say or what to do or where to sit. They’ll ask me questions, and then they’ll tell me that I’m stupid and send me home. I don’t want to go.”

I wish I could help him. I wish I could have told him not to drive to work that day in April, and instead to stay home with his beautiful wife and go for a hike like he’d wanted to. Savage Fat is very tired today.

PART TWO

Early on in our relationship, Edwin and I went with a group of friends to the Adirondack Mountains for eight days to camp, hike, and backpack. But mostly, we went to hit up Trap Dike: a bushwhack, rock scramble, and rock climb combo.

The Trap Dike, Photograper: Carl Heilman

Preparation had been a short video that Edwin sent to each of us. It was set to encouraging, upbeat music suitable for a leisurely kayak float, and they did not film any of the more difficult portions. Everyone maintained relaxed smiles and it appeared easy enough for the average hiker to tackle . If you find this video on the internet, do yourself a favor and be assured that it is not an accurate representation of the Trap Dike experience.

*Here are some links to videos that offer a better synopsis if you’re interested:

https://youtu.be/Tu90cvcWJPw by Brian_Hikes_All_Day

https://youtu.be/MYF1_RQhVLA by Mountain Life 603

https://youtu.be/owvw2bBbZC8 by Seth Baker

We had to play scheduling by ear based on the weather. Any inclement rain could wash out the ‘trail’ altogether, and us with it. The best day to set out happened to be our last, and it promised to be a warm one. The morning began with a two-mile jaunt on Van Hoevenberg Trail to Marcy Dam.

Historically, there have been countless, temporary dams built across Marcy Brook to create a large reservoir into which timber could be rolled for annual log drives. The water would swell, threatening to overtake its confines, and a mass of logs would bump against one another until the dam was dismantled and they could become something more akin to behemoth trout, bucking and heaving their way to the mills that had been built downstream. Many a man lost life and limb while ‘birling,’ the task of riding a rolling log downstream to help prevent jams. Birlers preferred Croghan boots with studded metal calks in the soles and heels for digging into logs. They would stand atop their mounts, balancing precariously and attempting to keep from falling into the churning timber.

Logging the Adirondacks, 1901-1921 New York State Archives

Adirondack logging was outlawed In the early 1900s, and the last dam placed across Marcy Brook was never removed when the site was abandoned. The reservoir became a fixture, earning the name Marcy Dam Pond, the area a destination for those who sought a spectacular view of three of the Adirondack’s iconic peaks, Marcy, Colden, and Algonquin. It also served as a base camp for those seeking access to the hiking trails that led into their heights, a welcome respite before and after a climb.

When the old dam fell into disrepair (it was never intended to be permanent), it was rebuilt with a wooden footbridge connecting the two sides of the pond, standing for years until 2011’s Hurricane Irene and her heavy rains. Marcy Dam and its famous bridge were declared a loss by state officials. To rebuild, it would have to meet ‘modern standards,’ a several million-dollar demand. The explanation of unaffordable expense satisfied most of those locals whose nostalgia had left them ‘heartbroken’ and lobbying for repair. But officials had another reason for abandoning the dam.

“There is a man-made structure… in the middle of a wilderness that was not functioning well,” said Dave Winchell, spokesman for the area.

“The views of the peaks will still be there. You’ll see them from a trail. And in (the pond’s) place…you’ll see a natural wild trout stream. And very hopefully wild trout will be able to reach their former headwaters, which is really an exciting prospect,” said Dan Plumley from Adirondack Wild.

John Sheehan of the Adirondack Council added, “This will not be seen as a drastic or unwelcome change by nature.”

A remaining piece of the old Marcy Dam, Photographer: Myself

So, Marcy Dam Pond drained away, its famous reflection made miniature in the brook that now flows across the site. The five of us sat on stones and bits of dam corpse, surveying its remaining bones, stained by thousands of gallons of tannin-laced water and sunlight. I liked the idea of real trout swimming through its ribcage. Looking out across what had been a lakebed, grass had begun to grow, miniature savannahs atop plateaus of sediment. The brook split into small and large branches, chattering over and between smooth stones. Nature was redecorating.

Marcy Brook, Photograper: Myself

The old lake bed. Photographer: Hope

After sharing a few snacks, we crossed a small bridge that had been placed downstream in a less flood-prone area and stepped onto Avalanche Pass. The trail sloped upward along an old creek bed. Megalithic stones and cliff sides created intermittent hallways and obstacles. Rag, Map, and Ribbon Lichen festooned their surfaces in chaotic patterns of seafoam, chartreuse, and sage green.

From Left: Edwin, Tim, and Tyler. Photographer: Hope

Boardwalks being overtaken by moss. Photographer: Myself

Tim on Avalanche Pass, Photographer: Hope

Knobby-kneed roots rose from the mud to become thin things that spread and tangled over the ground like ropey hair.

Hope, Tyler, and Tim, Photographer: Myself

Me on the boardwalks. Photographer: Hope

The forest parted at last, and sunlight streamed onto the banks of Avalanche Lake. They were littered with driftwood and mountain trash, but we weren’t looking at the ground anymore. Water flowed in a rippled line between the twin towers of Avalanche Mountain to the west and Mount Colden to the east. Trees upon trees dug their roots into the banks, clung to stone walls, and sat atop ledges. They had descriptive names like Mountain Ash, Sugar Maple, Quaking Aspen, Yellow Birch, and Pitch Pine. These names seemed to convey a personality, and it was easy to imagine them coming to life and wandering up the peaks for secret meetings in the night. They would, I think, speak a language of movement and odd music, their creaks, groans, whispers and rasps echoing over the water and stirring up tales of the bogeyman.

Avalanche Lake, Photographer: Myself

“Well, holy shit. That lake is beautiful!” exclaimed Hope. The soundwaves of her Ohio-heavy accent spread across the landscape. Her features are delicate, almost doll-like, but Hope is as rough and tumble as they come.

Edwin surveyed Colden’s cliffs, scanning their length with the special sort of longing that he reserves for bad ideas. “It would be awesome to side-climb that all the way to the base of Trap Dike,” he said.

My toes curled up in my minimalist shoes and I chewed on my lip. We weren’t going to try that, were we?

“Screw that!” Hope said, laughing. “That thing is crazy!”

I’d never felt more grateful to Hope, because with Edwin, you never know.

Avalanche Lake, Photographer: Hope

In ‘Guide to Adirondack Trails: High Peaks Region,’ Tony Goodwin described the next section along Avalanche Lake as “probably the most spectacular route in the Adirondacks.” Hiker Jonathan Zaharek said it a different way,

“You know, I look at how this was carved out, and it makes me think…I feel like this is where the glacier got constipated, and it had to just jjcchhhhuuuuu!…Right through this valley. And we got this lake because of that!”

From Left: Hope, Edwin, and Me, Photographer: Tyler

Fallen boulders littered the base of Avalanche Mountain, and we scrambled through the maze they created, aided by ladders and boardwalks. Two spans of catwalks protruded from the stony face of the mountain, hovering about four feet over the lake. They colloquially became known as ‘Hitch-up Matildas.’ In 1868, Matilda Fielding, along with her husband and niece, hired Edgar ‘Bill’ Nye to lead them on a hiking tour of the Adirondacks. Nye was a comedian and avid outdoorsman, and, when they arrived at Avalanche Lake, he carried Matilda on his shoulders around the western edge, her skirts hitched up as she clung to him.

From Left: Tim, Hope, Tyler, and Edwin on one of the Hitch-Up Matildas. Photographer: Myself

The second Matilda had developed a bit of an outward lean, and from this vantage point, we could look across and see the colossal rent that was Trap Dike. Even this close, it seemed more like a vague idea than a solid, climbable reality.

Trap Dike across the lake. Photographer: Hope

Bull, Northern Leopard, and Pickerel Frogs gave off vibrating croaks from the lake’s overgrown and mucky tip. Each of these frog varieties are lithobates palustris from the Greek lith, meaning ‘stone,’ and bates, meaning ‘one that haunts.’ Palustris is Latin for ‘in the marsh.’ Added together, you have the ‘stone one that haunts in the marsh,’ the most romantic title for a frog I can imagine. We filtered water here for the last time, sitting on logs and stones and breathing deeply. I think I would have happily turned around at this point or stayed and attempted to catch and identify those lovely frogs, but I wasn’t about to be the only one to bail.

Don’t be a scaredy cat, I told myself.

The far end of Avalanche Lake. Photographer: Tyler

After a moment of searching, Edwin found one of the nearly hidden herd paths on the eastern side. It was an overgrown tangle of branches and scrub brush, and after scrambling, ducking, and weaving, we exited onto centuries of avalanche debris. A pair of stone sentinel walls faced the lake shore on either side of a ruined staircase of gabbro and anorthosite that could have been carved by dwarves or ogres. Jagged lines of blue-grey plagioclase crystals wove through the stairway, and the walls themselves contained garnet veins that were the deep red of venison or the rust of old blood.

Garnet Vein in Gabbro, Photographer: Unknown

A Plagioclase Crystal, Photographer: Sascha Gemballa

It would be 0.8 miles and three thousand feet of elevation gain from here to the summit, with half of that being the slide. From down here, it didn’t look so bad.

***

Since that day, I’ve read numerous articles on Trap Dike, and all of them have this advice:

“If you cannot routinely scale a V4/V5 at the climbing gym, this is not for you.”

“We do not recommend free soloing the Trap Dike unless you are comfortable with exposure, are not afraid of heights, and have had sufficient training and experience climbing vertical rock and steep slabs.”

“This is the most dangerous hike in the Adirondack Mountains.”

And my very favorite:

“A fall on Trap Dike could, and has, resulted in severe injury or death.”

My climbing skills at the local gym are a solid and mighty V1, maybe a V2 on a good day.

***

This image belongs to Google.

We began our ignorant ascent, bounding up and over rocks and boulders. Hairy moss and dry grasses grew in patches of loose dirt and gravel. Water wept downhill to our left, and we avoided slippery splash zones, weaving from shade to rare patches of sunlight that warmed my skin. I was glad I’d worn shorts, leaving my legs free to bunch and stretch as needed. Handholds were plentiful, and after what felt like the first real bit of climbing, I allowed myself to wallow in a sense of accomplishment. Maybe I wouldn’t be exactly comfortable at this height, but I didn’t feel phobic.

From Left: Edwin, Hope, and Tyler at the Base of Trap Dike. Photographer: Myself

Maybe a quarter of the way up the dike, we veered into a dusty incline to avoid a larger section of waterfall. The ground slid beneath our feet with every other step, pebbles skidding to the edges of stones and off of blades of dry grass where they bounced down and down and down.

“Son of a biscuit!” Tyler said. Hope’s other half, Tyler is a classic, all-American boy with Pittsburgh engraved in his every syllable like the steel it’s known for. His ‘curses’ would be solidly at home in the heart of the Bible Belt, and I’ve always enjoyed watching him exclaim, “Hope! Not in front of the kids!” at our weekly ultimate frisbee games after she’s riffed off an absolute spree of f-bombs.

My calm somehow improved with these tame epithets, and blossomed further when Hope exclaimed, “What the hell are we doing up here? This is a hike for people with nothing to lose! This is stupid! I’m not going up this thing first. Someone else go.”

In a plucked-up state, I offered to plow ahead. When others are in crisis, my mind goes into this sort of numb, detached place in order to problem solve. I think it’s just what happens when you’re a mom, like a biological switch that flips the minute you give birth. I scurried up on all fours, trailed by the others and delighting in the view-blocking shrubs around me. No one noticed Edwin fall back. He’d decided to go around our boring route and skirt the promontory for a bit of extra climbing. He moved hand over hand, but when he rounded the stone’s edge, he was met with a sheer cliff face. Climbing back and down wasn’t a safe option, but neither was going forward. Edwin weighed his options and settled on following through with his plan. He picked his way over what had become a V5 free solo, his day pack suddenly an awkward encumbrance. He looked down, and for an instant, he could picture himself falling and hitting the rocks below like a piece of meaty scree. He imagined that we would all wonder where he was, and when we went to look for him, we’d find him dead or dying. He tightened his grip on the stone before reaching one arm out, his fingers feeling for the next hold. Maintaining three points of contact at all times, he followed his arm with a foot, and he wished he were wearing climbing shoes. By the time he made it across and caught up to us, he was already over it and smiling that classic Edwin smile. It’s a mad rectangle of teeth, like a kid cheesing.

Edwin’s father offered up few compliments and little approval while he was alive. The rare deviations from that pattern almost always followed a risky move. Caving, whitewater rafting, dangling from heights – this is where they bonded. One of the first things Ed senior ever said to me was, “I’m an adrenaline junkie. I’m not afraid of anything.” Those words were repeated again and again, almost every time I saw him. If Edwin wanted love, he could get it by being the closest one to whatever edge the two of them bordered, and his father would say, “That’s my boy.” Sometimes I wonder if Edwin is still looking for love when he risks himself this way. From his dad or from a world that hasn’t always been kind. Like, maybe if he does a handstand on a crumbling cliff four thousand feet in the air, the universe will say, “That’s my boy.”

Edwin, Photographer: Myself

Tyler laughed with relief and amusement, and Hope seemed to relax, leaning back against the trap’s side. Tim merely shook his head. He’s a quiet man, ready with the occasional sarcastic crack or perfectly timed side-eye, and in the mornings, I know that if I don’t see him stoking the fire that he’ll be inside his tent, reading. The group’s return to ease resulted in the flooding back of my own discomfort; my dubious superpower lost. I must admit, in that moment and several others, that I selfishly wished at least one other person would fall apart so I could return to my functional lobotomy.

From Left: Myself and Tim. Photographer: Tyler

By the time we reached the first V4, my limbs were getting watery. I wasn’t tired; I was scared. I froze halfway up, my arms wrapped around a boulder, clinging to hand holds that I knew were perfectly safe, but felt too far apart.

I hate this, I thought. I glared at the rock, my eyes less than an inch from its surface. I hate you. I hate your rounded surface that makes me feel exposed and vulnerable. I hate your height and your position on these wretched ogre stairs that allows me to see the puddle Avalanche Lake has become from this distance.

I made pathetic whimpering sounds while Tim grabbed hold of my foot, pushing it into the rock and guiding me upward. Edwin offered encouragement from above and Hope offered advice from below. I wanted to refuse the whole thing, like a kid at the dinner table who wouldn’t eat her nasty squash casserole. It’s not so much that I’m afraid of heights. I’m afraid of myself near heights. My body and mind experience an awful sort of disconnect, and in between the two is firmly wedged L’appel Du Vide, The Call of The Void.

Associate professor of psychology at Miami University, April Smith, says that The Call is experienced in differing degrees by about 50% of the population, and is a result of the brain miscommunicating with itself. She believes that our minds set off an alarm when in a state of perceived danger, telling us to increase awareness, to perhaps step backward or forward to better observe our situation. We then analyze this step and assume that it was a desire to self-destruct. This is not so, she assures. The Call is nothing to worry about. This leads me to believe that April has never felt L’appel Du Vide herself. If she had, she would know that the Call feels less like a helpful alarm and more akin to Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, the Zombie-Ant Fungus.

These cordyceps begin as a single celled organism, invading a host ant’s bloodstream where it will begin to replicate. They then build tubal bridges that allow them to connect, communicate and feed one another until they can grow into a network that slithers from muscles and joints to surround the brain. The ant’s consciousness, whatever such a thing may be, remains intact as a hostage observer. Its body is corrupted and subverted until this living puppet is forced to climb up and away from its community. Its mandibles will permanently lock onto the vein of a leaf, rooting it wherever humidity and temperature provide the optimal atmosphere for fungal birth. A pale, fleshy tentacle will slowly begin to emerge from the base of the ant’s head, growing until it is mature enough to support a globular capsule filled with hundreds of spores that rain down upon the colony below.

Zombie-Ant Fungus, Photographer: Unknown

Here, on Trap Dike, I could feel my muscles jerk under the influence of my own personal zombie fungus. The urge to push away from the safety of my colony and seek out extinction was an awful thing. I bit the inside of my cheek to tether myself to the moment and forced myself to climb. When I made it to the top of the first crux, I saw the rest of our group exchange uneasy glances. I knew they were (understandably) wondering what they would do if I seized up on the mountain. It’s not like they could carry me. After a few awkward moments, Tim forged ahead, Tyler and Hope following close behind. They didn’t look back as our small groups gradually separated, and I felt the loathsome shame of being the weak link.

Edwin on one of the more level areas of the dike. Photographer: Tyler

Edwin jumped from rock to rock beside me, saying, “I love this! It’s absolutely perfect. I’m so glad we came!”

I looked at him, blinking slowly, and tried to muster a feeble smile.

The rest of the climbs weren’t nearly as terrifying and only plucked at the edges of my fear instead of tearing it wide open. Even the second crux, a steep forty-foot waterfall, bothered me less, though if I had known its history I may have felt differently.

***

On September 20, 2011, a hiker named Matthew Potel was leading a climb up Trap Dike with 7 members of the Binghamton University outdoors club. Two women in the group were having trouble climbing up this crux, and Potel went back to help. He managed to get one of them up and over, but as he was reaching for the last person, he lost his footing and fell 25 feet to land headfirst in the ravine. He suffered a major cerebral hemorrhage on impact. Some members of his party were able to make a call from the slide, and local rock climbers helped the Forest Rangers recover his body. He was twenty-two years old, and a 46er – having summited all 46 Adirondack peaks taller than 4,000 feet.

On March 16, 2022, 63-year-old Thomas Howard parked his car in the Adirondack Loj lot and entered his name into the trail registry alongside his intended destination – Mt. Colden via the Trap Dike. He had summited Mt. McKinley, Huascaran, Xixabangma Peak, and Mt. Kenya. He had hiked the entirety of the Appalachian Trail, the 273-mile-long trail in Vermont, and crossed the White Mountain Presidential Range in one day. Twenty-seven rangers in sled and foot operations and state police via helicopter searched tirelessly for three days before they found him at the base of the upper waterfall. He was buried beneath 4 feet of snow from a suspected avalanche.

Trap Dike Search and Recovery, Photographer: Howard DEC

There have been others, of course, but deaths are rare. Far more common are rescues, and the causes are varied: injury, exposure, lack of preparation, and paralyzing fear.

***

The first and older of the two slides appeared on our right. It was varying shades of grey and beginning to grow over. This had been the preferred route up until the same hurricane that took out Marcy Dam also created the Irene Slide. Lying ahead, she was a fresh white anorthosite – the same calcium rich stone thought to make up the crust of Earth’s moon. A crack ran up and across her surface, and I set my hands into this narrow hold, bringing my body as close to the her as I could manage. I thought about lifting my feet up and bracing them against the slide, and I tried this move a few times. They slid down. I was too afraid to lean away and provide enough pressure and friction to hold my feet against the grippy anorthosite. I put my feet up and down, flummoxed.

The Irene Slide Begins, Photographer: Tyler

Tim, Tyler, and Hope were long gone, and Edwin had had to choose between mapping out our route and staying behind to be my support system. He stayed behind and made a step for my foot out of his bent leg.

“Love, you can’t go back,” he said. “You have to go forward. That’s the only way out of this.”

There is no try, only do. I remember thinking that my Yoda was very annoying, and I decided that didn’t want a mentor anymore. I wanted Edgar ‘Bill’ Nye with his convenient shoulders and lakeshore comedy. I wanted anything but this relentless climb.

I’m pretty sure that I snarled and growled my way up, gripping the mountain’s pebbled side with my knees and feeling skin tear away. The feeble smile I’d mustered half an hour ago became an awful, painted-on thing. My teeth were clenched, and a string of endless profanity ran through my head. I was furious. This mountain and I were not friends. As we ascended, the exquisite MacIntyre Range came into full view at our backs, but my world had shrunk down to nothing more than the rock in front of me.

Tyler and Hope on the slide. Photographer, Tim

At the earliest possibility, I darted into the miniature forest that clung to Irene’s left side. Thick, low pines, scrappy bushes, and spiked deadfall created a matted tangle called ‘cripplebrush.’ I grasped at branches and trunks, pulling myself through the tangle. Blood ran down my legs now, smearing white branches when they slap-scratched against my skin. They looked like wolf teeth, and I felt a sort of raging satisfaction. Irene might be snapping at my heels, but she wasn’t going to take me.

I moved in and out of these jaws, venturing onto the slab only when the cripplebrush became too thin and loose. It was an erratic pattern, and my adrenaline crutch dwindled along with my somewhat dramatic commitment to victory. I started to feel like a blown deer, capillaries bursting in my nose and misting the air with red droplets. I was being run down, and all I wanted to do was sleep, the shrieking of my exposed nerves acting as a bizarre white noise machine.

None of that, I thought, and I imagined kicking out with sharp black hooves against Irene’s pale wolf hide, force-feeding the image to myself until it could become fuel.

“Hey, take my picture,” Edwin called out.

My head swiveled and I stared at him. Seriously? How was I to stay feral enough for survival while doing something so… mundane? I pulled out my phone with one hand while the other clung to a blackened pine root. This modern and thoroughly useless item looked ridiculous in my hand. I snapped some photos, and he said,

“Not that angle. You won’t really be able to see how steep it is. Can you turn the phone and get down low?”

Of course, dearest, I thought. Anything for you. I got what I thought might be something workable. It was hard to care while my head had rested blissfully on a patch of moss. I jerked up before the spongey mass could become a long-term pillow. I could tell that dirt had stuck to the side of my face and pieces of loam hung in my hair, swinging like spiders on silk. Sarcasm spent; I considered my husband. Was I ruining this adventure for him? He took a few easy steps and paused to look out over the rippling landscape. He exclaimed over the varied, splendid features of my foe, and pointed out peaks and waterways. I decided that this meant it must not be ruined.

Edwin on the slide. Photographer: Myself

I envied his fearless abandon, but I was also sort of proud of it. It’s a sumptuous thing to admire one’s mate, and not everyone is so lucky. Edwin had poured countless hours of his life into understanding the human body the way a geologist might understand the formation of the slide we now climbed. His movements were efficient, smooth things. He didn’t worry about falling, because if he did, his body would know what to do, where to tuck and where to spread to create the best possible outcome. He trusted it in a way that was foreign to me. I smiled my first real smile in what seemed like a very long time, and he smiled back.

I borrowed this photo of Matt McNamara coming up the slide, because I didn’t get anything that felt as though it truly captured the steeper grades. Photographer: Josh Wilson. I hope they don’t mind!

A spot to rest before continuing up. Photographer: Tyler

Irene’s final assault was hurled when the climb was nearly over. I was forced once again out of my chosen hell and back onto the slide where it had not only become steeper, but slick from the water that seeped out of Colden’s crown. I thought about how this would be the worst place of all to go down, and allowed myself a moment of panic before moving on. It was only about ten feet up and another seven across to the goat path that led to the Mount Colden Trail.

Tim, Tyler, Hope sat waiting there for us, and I settled in beside them, shocked that the worst was over. It made me feel a little bit better to learn that Hope had reached the peak and immediately vomited into a patch of huckleberry bushes. I listened to her story with my gory legs stretched out. No hooves. No fur. Just human things.

On top of the Irene Slide. Photographer: Myself

Hope fell silent, and we watched a couple make their way along the official trail. An American Labrador trotted beside them, its pink tongue lolling. It sniffed the air and began to rummage through the brush. I don’t know why we didn’t warn them about what was obviously about to occur. We just watched like a quintet of mutes as it reached THAT SPOT and began to gulp and slurp Hope’s stress-purge with cheerful abandon.

“Oh,” Hope said finally. “I puked there.”

The male half of the couple dragged back on the leash in horror as the Labrador fought to return to its feast. The three of them struggled downhill, trotting and tripping over themselves in an effort to leave us behind.

“It was a well-balanced breakfast!” Hope called after them. “Apples’n oatmeal! Probably not that bad for ‘im.”

They didn’t look back or respond. Edwin loped off to tag the peak of Colden, and I creaked my way into a standing position to follow him before we began our six mile descent to the car. We passed a group of hikers who had been up the Trap Dike just before us in matching t-shirts, climbing helmets, and coiled circles of rope slung over their shoulders. They looked very prepared. Everyone we passed stared at my legs, and several people asked if I was ok. I nodded.

“I’m fine,” I lied.

The Mount Colden Trail is thin, often slippery, and boulder laden. I noticed my left knee twinging with each down-step and climb. Twinging became pulling, and pulling became serious pain. I had been so tense going up the slide that my seized muscles were now pulling on ligaments and tendons, telling me that they’d had enough.

Back to the easy Van Hoevenberg Trail. Photographer: Tim

I hobble-hopped the miles back with Edwin’s help. I don’t really remember the drive home, but I remember the shower at Edwin’s friend Otto’s house. The water stung, and I set the heat up high enough to turn my skin a bright pink. I remember a note tacked to Otto’s refrigerator that said, “If Lena’s ok, you’re ok.” Lena was eight years old, and Otto had gone through a difficult divorce and custody battle. I stared at the note for what seemed like a long time. I felt it in my bones. I remember nestling into a down blanket by our campfire as the sun set and feeling hollowed out and glazed over. I remember thinking I would fall asleep so fast, and then laying in my sleeping bag, listening to Edwin snore, my legs contracting like they were still trying to climb, to run. A skunk nosed somewhere in the wooded back lot, and crickets scraped out their rusty songs. The nighttime cries of frogs and the whisper of trees would be lifting from Avalanche Lake to flow through Trap Dike and over the Irene Slide right now. All of that fresh white anorthosite would be gleaming, the moon’s little sister. I found myself wanting to go back there to soak my legs where waterfall trickled into lake like a pack’s worth of chilly wolf tongues. My hatred for that space had been nothing more than a hatred for my own pain. I think what I really wanted was to say thank you to the mountain that had watched me struggle 50 times, ignored my complaints and commanded me to rise, shake off the dirt and doubts, and continue.

Instead, I curled onto my side and pushed my nose against Edwin’s shoulder. It was warm under his Long Johns. I draped one arm over his chest. My breathing slowly shifted to match his and I fell asleep to the feel of his heart beating under my fingers, each of us inhaling the Adirondack air.

Edwin and I enjoying our last wade into the cold Adirondack water. Photographer: Jamison

PART ONE

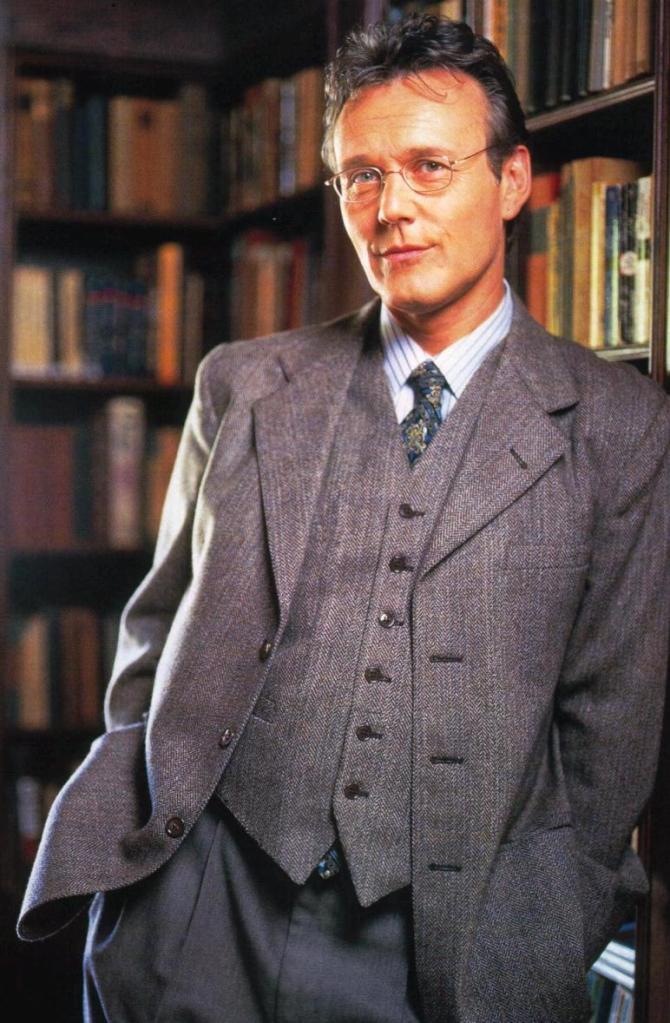

I grew up, as so many people did, watching and reading about training montages. The Empire Strikes Back, Taran Wanderer, The Karate Kid, The Hobbit, Sabrina (not the witch, though that probably applies), Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken, Cool Runnings, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, etc. (most of which I was not allowed to watch or read, but did so anyway, because I needed to know about more than plants, birds, and theology to socially survive). I’m sure I’m not the only teenager who imagined a version of my life in which Giles descended from a fabulously well-stocked library with the sole purpose of making me BETTER, whether I liked it or not.

Rupert Giles, Promotional Still From Buffy The Vampire Slayer

I longed to be a heroine in life. I wanted purpose to be thrust upon me in an obvious and visceral way. I wanted trophy bruises and scars that I could count in the bathtub the way I counted mosquito bites and the scabs I earned from climbing our sprawling yew tree. I wanted to know my body’s limits and then test them again and again. I wanted to speak foreign languages, stalk game, develop stupendous ninja skills, and have ‘true grit.’ I wanted to be elegant and collected and desired, a jaguar in Givenchy. I wanted to sink my teeth into life and tear out its heart.

However, all of these seemed elusive fantasies. I had no idea how to acquire them on my own. Where was my mentor? The one who, when I got angry and wanted to give up after falling for the fiftieth time, would ignore my complaints and command me to rise, shake off the dirt and doubts, and continue.

My family didn’t have much money, so I only ever dabbled in this or that activity long enough to see a glimmer of promise before entering barren periods of lethargy. It’s not that my parents allowed me to be a slug; I simply didn’t have a physical disciplinary practice to engage in. I’m quite sure I contributed to those empty spells by whinging and avoiding practice because learning wasn’t as fun as I’d expected it to be. When you are poor, and you’ve scraped together your pennies to give your offspring an opportunity, it’s hard to withstand complaint. I understand this. I’ve been there, and I’ve pulled my own children out of classes and perpetuated the cycle. Knowing that I could provide better meals or Christmas presents if I no longer supplied those resented lessons was a powerful argument in favor of abstinence. I had holes in my sheets, and I acquired our produce via the plants for sale in the garden center at Lowes, stuffing them into my shirt like contraband. I gathered greens from the back yard and mushrooms from the woods, and sometimes dinner was still a box of Kraft macaroni and cheese. My home had no heat or air conditioning. Child support wasn’t consistently coming in, and government assistance was slow to authorize and maintain. What was I doing sending my children to gymnastics?

As a child myself, I was thoroughly ignorant of the struggle. Why was no one saying: “You can do this. Get up and move. I don’t care if you don’t want to do it right now; you will tomorrow. If not tomorrow, then the next day. Years from now, you’ll look back and you’ll have a skill. You won’t be afraid to try new things. You will trust your body, your mind, and your instincts because you’ve trained them.” I wanted Yoda with his, “There is no try, only do.” I wanted someone to believe in me so much that they didn’t listen to me. Maybe not everyone felt this way. Maybe no one else did. Perhaps I was a contradictory and irritating soul. The last is probably true, but not the first two. As much as we make ourselves lonely and think that no one will understand certain parts of us, we are not so special. At least some of you will probably know what I mean.

With hindsight, I can clearly see that I lacked discipline in a massive way. At any point I could have borrowed library books on foreign language and forced myself to learn. I could have developed a dubious exercise program or practiced my ninja skills by kicking that old yew tree 10,000 times, to borrow from Bruce Lee. Many remarkable children have trained themselves to become even more remarkable adults, but I wasn’t one of them. It was easier to blame a missing road map than to blame myself for having a lazy spirit.

During those formative years, my personal training often involved making and breaking promises to myself and setting and abandoning intentions, creating a pattern of giving up or giving in. When a human being is challenged, it always falls back on its training. So, when life got hard, I fell back on mine, and either clung to things that should have been released or ran away from things that should have been held onto. Luckily, life presents a myriad of opportunities for overcoming every day, and we can choose to re-train.

When you want to create a new life pattern, it’s important to understand where the old one came from. Why are we doing things this way and not that way? How much is nature and how much is nurture? Looking at my own habits, some of them are personal, based in my particular family and genetic makeup, but others are widespread, societal things.

The root of societal laziness and fear seems to come from the avoidance of pain. We no longer ‘come of age.’ Most of us did not and do not have elders in our families or communities to teach us how to transition from childhood to adulthood, and so we just sort of…don’t. We stay in our hedonistic, adolescent larval stage, avoiding the cocoon of transformation because it doesn’t feel good.

***

In the Brazilian Amazon, the Satere’-Mawe’ tribe will search the humid, lowland rainforests for paraponera clavata, more commonly known around the world as the bullet ant. Locals refer to them as ‘hormiga veinticuatro’ or, in English, the ‘twenty-four-hour ant’, referencing the long-lasting pain induced by a single sting. The Satere’-Mawe’ call them ‘tucandeira’, meaning ‘that which wounds deeply.’

On the Schmidt Pain Index (a rating scale from 0 to 4, with zero being no pain at all, and 4 being excruciating), the bullet ant ranks as the only insect to rate beyond a 4. Schmidt himself, the entomologist who has endured countless bites and stings from various insects over the course of his career, described the sting of the bullet ant as “pure, intense, brilliant pain. Like walking over flaming charcoal with a three-inch nail embedded in your heel.” Their sting releases poneratoxin, a paralyzing neurotoxic peptide that interferes with nerve cells’ ability to send signals back and forth. This causes slow, long-lasting contractions of mammalian smooth muscles, cold sweats, nausea and vomiting, extreme pain, and arrhythmias of the heart.

Bullet Ant, Image Provided By Adobe’s Macroscopic Solutions

Once collected, a Satere’-Mawe’ medicine man submerges the ants in a sedative of crushed cashew leaves before they are woven, stingers pointed inwards, into palm-frond mittens. There are, on average, 80 to 200 ants in each mitten pair, depending on the tribe and size of the mittens. Less than an hour later, the ants awaken angrier than ever, and the Bullet Ant Ceremony begins.

Boys as young as 12 will participate, lining up at a sort of bamboo bar, hands upraised in crab-claw poses, heads bowed. They must wear the gloves for more than ten minutes, submitting to the writhing insect host without crying aloud. They may sing or chant, but never scream in weakness. To help them meditate through the pain, the boys are led in a ceremonial dance, their arms linked to form a line, each one helping the other remain upright.

Once the gloves are removed, the pain only intensifies as the poneratoxin spreads. Initiates may take up to a week to fully recover, sometimes spasming for days. This agony symbolizes their readiness for manhood. The point is not to wall yourself off from pain, but to thoroughly understand it, accept it, and learn from it. Strength and stamina are required to survive in the jungle. “If you live your life without suffering anything, or without any kind of effort, it won’t be worth anything to you,” a Satere’-Mawe’ chief said. Each boy will wear the gloves 20 times over the course of several months before the initiation is complete.

Thanks to YouTube, the Bullet Ant Ceremony has become a major tourist attraction, drawing would-be macho men from around the world who pay to participate. They nervously crack jokes about the silliness of it all, or they roar like human bulls, trying to psych themselves up for the challenge. Some swagger and boast, and only a rare few quietly and respectfully engage to the best of their ability. They move into position with their borrowed headdresses and painted hands like children playing dress-up. Almost all of them fall rapidly apart with shrieks, swears, weeping, and wild flails. They are taken to the local hospital, shrilly demanding pain relievers.

The Satere-Mawe smile. Thank you, come again.

Bullet Ant Ceremony, Photographer Unknown

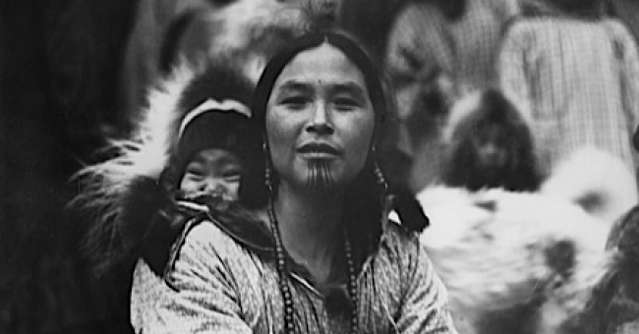

North Baffin Island in the territory of Nunavut is covered for most of the year in snow and ice. Because it is so close to the Arctic Circle, there are six annual weeks where the sun does not rise, and darkness reigns over the land. Great winds create blizzards that turn inland waterways into icy land masses. Years ago, the Inuit hunted seal and narwhal on these masses for meat, hides, and fat, which provided the extra calories needed to withstand the extreme cold. In June, birds returned to lay their eggs on the tundra floor, providing a welcome change in nourishment. In August, the Inuit followed the caribou who had travelled through on their annual migrations. Their meat was frozen and stored, and their hides provided new winter clothing, sewn and decorated by the women.

These days, the people are tired and disenchanted, disease and starvation having dwindled their numbers and spirits. They must make compromises between modern technology and old traditions. Igloos and animal skin tents have been replaced by government housing, and snowmobiles are favored over sleds. Noise from motorboats, snowmobiles, seismic testing, and rifles have frightened away much of the game, and the Inuit say that the trust between humans and animals has broken down.

North Baffin Island, Photographer Unknown

Their shamans are rarely called upon to explain the world and its balances because young people no longer care for their ‘wisdom.’. Exposure to the internet hive mind and the harsh reality of their own existence has disenfranchised them with spirituality, their trust in religious leaders replaced by the words on their screens. Elders fear the loss of culture, tradition, and the strength needed to survive such a harsh landscape. They have begun to revive coming of age ceremonies. The shamans are being asked once more to open the lines of communication between man and animals before boys go out into the wilderness with their fathers or grandfathers. There they will practice and test their hunting skills as well as their resilience and adaptability.

Young women are engaging in a rite of passage in which they receive Tunniit, facial or thigh tattoos that signal a readiness for adult responsibility through the pain of transformation. To receive Tunniit, one must master difficult, essential skills, proving one’s value to the tribe and a future family. The design of the tattoo may differ for the individual based upon the community she is from, but each one represents some form of beauty attained through courage and endurance.

Tunniit, Photographer Unknown

In Vanuatu, a small island nation in the middle of the Pacific, young boys jump from a 98-foot tower with a bungee-like vine tied around their ankles. Unlike a bungee, however, the vine lacks elasticity, and the goal is to come as close as possible to brushing their heads on the ground without dashing them in. Boys begin jumping at the age of 7 or 8 from a smaller tower while their mothers hold an item representing their childhood. When the jump is completed, the item is thrown away, symbolizing the end of childhood and the beginning of facing one’s fears.

The Vanuatu Jump, Photographer Unknown

Apache girls participate in a Sunrise Ceremony or ‘Na’ii’ees’. These four days represent the baby, children, and teens they have been, and the women they will become. They run laps every day, memorize native plants and their uses (Apache women have always been healers), and dance for hours. On the fourth night of the ceremony, the girls will dance from dusk until dawn. Exhausted once the sun rises, they run laps once more, and on the fourth lap they run as far into the wilderness as they can before returning. Their families run with them, shouting encouragement to the staggering girls. The farther they go, the stronger they will be in life.

Na’ii’ees, Photographer Unknown

Aboriginal boys between the ages of 10 and 16 go on Walkabout, an excursion into the outback that lasts six months and hundreds, sometimes thousands of miles.

Walkabout, Image By Nicolas Roeg, 1971

The Mentawi tribe of Indonesia files the teeth of young girls aged 10 – 14 into points using nothing but a chisel and elbow grease.

Tooth Filing, Photographer Unknown

And on and on it goes. At least, for some. I come from the modern United States. Some of us are the YouTuber’s paying to shove ant mittens on our hands and squealing for a few likes, and some of us are truly exceptional. Most of us are the pain avoidant creatures I mentioned earlier who will pay any price to have our aches removed.

In 1974, the philosopher Ivan Illich published a book called “Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health.” He wrote:

“When cosmopolitan…civilization colonizes any traditional culture, it transforms the experience of pain…People unlearn the acceptance of suffering as an inevitable part of their conscious coping with reality and learn to interpret every ache as an indicator of their need for padding or pampering. Traditional cultures confront pain, impairment, and death by interpreting them as challenges soliciting a response from the individual under stress; medical civilization turns them into demands made by individuals on the economy, into problems that can be managed or produced out of existence… Culture makes pain tolerable by interpreting its necessity; only pain perceived as curable is intolerable.”

“Patience, forbearance, courage, resignation, self-control, perseverance, and meekness each express a different coloring of the responses with which pain sensations were accepted, transformed into the experience of suffering, and endured. Duty, love, fascination, routines, prayer, and compassion were some of the means that enabled pain to be borne with dignity… Now an increasing portion of all pain is man-made, a side-effect of strategies for industrial expansion… It is a social curse, and to stop the “masses” from cursing society when they are pain-stricken, the industrial system delivers them… pain-killers… Pain has become a political issue which gives rise to a snowballing demand on the part of anesthesia consumers for artificially induced insensibility, unawareness, and even unconsciousness… Pain loses its referential character if it is dulled, and generates a meaningless, questionless residual horror… (It) turns people into unfeeling spectators of their own decaying selves.”

Ivan Illich

We are oh so cosmopolitan here in the U.S.A. Just like Jason Calhoun’s rats and mice from Chapter 1 in their ‘Utopias,’ we are slowly becoming ‘spectators’ as Ivan put it. We have succeeded in monetizing our pain and making our every ailment curable, both physical and otherwise. If it hurts, something is wrong. Medicate, rest, distract, escape. We pop ibuprofen (or something stronger) for our headaches, purchase office chairs with ever-increasing cushioning to support our atrophied bodies. We build ‘safe spaces’ in public areas and apply ‘trigger warnings’ to our thoughts. We handle one another and ourselves with kid gloves that smell of latex and antiseptic.

I work remotely, answering the phone for a housekeeping company, and I cannot begin to impart how often people experience discomfort and believe themselves to be sorely injured, ill, and unable to work simply because they have never before exerted themselves. They flee their job sites after experiencing an increased heart rate, rapid breathing, nausea, over-heating, and lightheadedness, certain they are coming down with the flu, covid, or having heart attacks at age twenty. One young woman called out because her arms were sore from running a vacuum the day before, and it was a new sensation for her. She had spent the entire night icing, heating, and rubbing various ointments and balms into her limbs, sobbing in a sort of sleepless delirium.