In April of 2022, I got a call from my sister, Caitlin, telling me that our father had been in a car accident. He’d been taken to VCU’s Critical Care building with a head injury. I spent the day on the phone with my siblings and mother, twiddling my thumbs and waiting for news. That’s the downside of living in a different state; you can’t pop over during a crisis because travel requires planning.

I got permission from the schools to pull both kids out for the rest of the week. I coordinated with Edwin and checked in with work. The girls and I left the next day. We didn’t realize that minors under sixteen are not allowed to visit the ICU. I didn’t know that children who have dying mothers and fathers and grandparents are not allowed to say goodbye. They must sit in the waiting room, peering down the hall every time the corridor door swings open, willing their goodbyes along fluorescent pathways. There were a lot of things I didn’t know then.

The girls stayed with my brother Neil, and I ventured on to the hospital to meet my mother. All told, my father had several brain bleeds, multiple skull fractures, and a fractured and broken right orbital socket that was impinging upon his optic nerve and severing the flow of blood to his right eye. His neck and low back were fractured in multiple places, his right lung was collapsed, his right shoulder was dislocated, most of the ribs on his right side were fractured or broken, his pelvis had multiple fractures, his right patella was cracked, right femur fractured, and right foot fractured in multiple places.

He arrived without identification and was given the name XE Cento as his ‘John Doe.’ They estimated his age to be between 64 and 65 based upon appearance and vitals. He would be 75 in four months. My father had been a strong and healthy man.

My mother holding my father’s hand.

He slept for almost a month. We watched his facial expressions and the monitors with intensity. The numbers all meant something, and it was all we had to tell us whether things were getting better or worse. He stopped responding to commands and painful stimulus. AFIB was in and out. His blood pressure was good and bad. The swelling in his brain waxed and waned. Procedures came and went. The room smelled like old blood and plastic. Wires, tubes, and drains flowed from him like something from Star Trek.

‘We are the Borg. You will be assimilated. Your uniqueness will be added to our collective. Resistance is futile,” I could hear him joking in my head. Star Trek had been ‘our show.’

I had a playlist on my phone called, “My Dad’s In a Coma.” It had songs like ‘Golden Slumbers’ by The Beatles, ‘Call It Dreaming’ by Iron and Wine, ‘In The Arms Of Sleep’ by The Smashing Pumpkins, ‘All I Have To Do Is Dream’ by The Everly Brothers, and ‘Sound-A-Sleep’ by Blondie on it. I’m not sure why I did that.

I stared at his eyelids, one of them purple, bloody, and unable to close over an eye that looked like an over-sized, gelatin-filled bouncy ball. and the other as normal as it had ever been.

‘Open your eyes, open your eyes, open your eyes,’ played on a loop in my head.

I sang the songs he used to sing to me when I was a child, and I didn’t want to get out of bed. He would leap up and down on my mattress, shouting the words to ‘Morning Has Broken’ by Cat Stevens and ‘Good Morning’ from Singing In The Rain. As a child, I’d bounce and shriek like mad. It was my favorite way to wake up. He didn’t wake up.

His nails got longer and cracked at the edges. His hands and feet swelled from the saline and medication drips. His cauliflower ear went back to its normal shape. His right eye slowly descended back into its socket, and I stopped worrying that it would rot and run down his cheek like awful jam. I read The Fellowship of The Ring to him, nattering on about how he was like Frodo right now, and we were his Company. Neil, the oldest of us, would be Pippin: charming, smoking his pipe-weed, and somehow able to make every nurse laugh and feel at ease in spite of the gravity of the situation and the fact that it was tearing him apart like Saruman’s Palantir stone. Laura, next in line, would be Legolas: elven, unyielding, her clear and perfect voice filling up the hospital room. I suppose I would come along then, but it’s hard to see oneself, and I was too tired to try. Caitlin would be Boromir: full of a love of home and family and so devastated by impending loss that she had to stay away.

My mother was Sam, of course, never leaving our father’s side and urging him on. She put tea tree oil on his toenails ‘so they would look nice for the beach.’ She moisturized his face and legs. She told him how handsome he looked and how much she missed him. She prayed for him and held his hand and watched everyone who entered the room like a hawk with rabies (I don’t even know if hawks can get rabies, but if they can, I’m sure that was what it’d look like).

We watched the patients in the halls. Some of them were walking assisted, others were sitting in wheelchairs, and yet others lay on gurneys with their heads moving back and forth so they could see their surroundings. We would have given anything to have my father be one of them, any of them.

We did our best to stay upbeat. We played classical music and danced. We made faces out of the windows. We threw bits of band-aid wrapper at each other. We talked about memories and things we would do differently when…if…my dad woke up. We waved sad, limp hospital lettuce at each other. We laughed so hard that we couldn’t breathe. We also cried. We cried a lot.

Manic moments in the hospital room.

Edwin’s own father had passed away several months before the accident. They’d had a complicated relationship, and in true-to-form fashion, his death was equally complicated. There wasn’t a funeral. It took months just to receive a cause of death. Surprises came and went. I think Edwin truly wanted to be there for me. He would pat my back in a sort of absent-minded way, and he suffered my frequent absences with patience. He asked me how I was once. I only remember it because the question startled me. For the most part, my husband was an ill-tempered ghost. The whole world irritated him. He barely looked at me. He wandered off in the middle of conversations, staring straight ahead as if in a dream. The man who had joyfully frolicked across a bog only a handful of months earlier seemed like something from a dream. This isn’t fair, I remember thinking. Why can’t we take turns with our tragedies?

Life isn’t always interested in fairness. In some strange and inexplicable way, the unfairness of it all was sort of acceptable. Maybe Edwin couldn’t talk to me about his feelings, and I couldn’t cry in front of him. Maybe he didn’t want to touch me, or even kiss me, and maybe I couldn’t provide a warm, clean haven of a home. but we had something else. The sadness in me saw the sadness in him. We grieved near each other, two moons orbiting around the same lonely planet.

And then my father woke up. It wasn’t all at once, like in a movie. It happened on a weekday, so I was back home in Pennsylvania. Neil sent excited messages and called to share the details, painting a picture for me. One eye opened, and then the other. It was only for a moment or two at first, and then longer. He would track the people in the room in a sort of fuzzy way. He couldn’t speak. He couldn’t move more than a little. But that didn’t matter; he was awake.

Taking a break outside with the kids.

It has now been almost two years since the accident. My father has thrown food at me – a sort of pureed blend of pork, peas, and rice that smelled of feet. He has whispered a desire to give up, to go insane, to die. He has poured his own urine on his head like a terrible baptism. He has screamed in pain. He has forgotten the words for common-place items. His hands have been like claws and his muscles have atrophied in extreme ways. He has called my mother a creepy old woman, and she has run from the room weeping out of exhaustion, loss, and hurt. He has looked at me the way he looks at his nurses, a kind stranger in a strange land. He has told me that I am not his daughter. He has called me on the phone to ask who he is. He doesn’t want to know his name, he wants to know who he is supposed to be, and what sort of purpose his existence fulfills (don’t we all). Somehow, he has believed that I’ll have the answer. He has cried with his mouth wide open, great sobs shaking his body. He has been trapped in the past, 30 years ago, ten years ago, five years ago. He has ignored the girls when they were able to visit, refusing to look at them and waving them away. He has perseverated on his trach, his feeding tub, his catheter, his blankets and socks and bed pad and anything else in reach. He has confused utensils, trying to use a spoon as a straw and a straw as a toothbrush. He has talked in loops for twenty minutes at a time, saying things like, “I want fish food,” “I want to trade animal flesh for some man flesh,” and “How do we know if new things are new?” He has hallucinated a monkey, a small white dog, a kitten, snakes, insects, and family members. He has had no desire to share his food, drinks, or blankets with my mother, whom he once shared everything with. He has talked over and interrupted everyone. He has believed himself to be the next President of the United States. Over and over, he has read aloud the sign that states in large, easy letters,

“Your name is Gordon Frantzich.

You were in an accident.

They are ok.”

Sometimes when he has read it, tears have rolled down his cheeks in steady waves. Sometimes the tears have been for what he has lost. Sometimes they are out of relief that he didn’t hurt anyone. This has made me angry.

***

He was driving sixty miles per hour, the speed limit, when Anna Chavez-Maples drove through a stop sign at a major intersection. She was going fifty miles per hour, speeding on her own road, when she hit him. The officer who arrived on the scene asked what happened after my father was taken away, and she replied,

“I didn’t have my morning coffee.”

Several days later she put up a Facebook post. I know, because every member of my family seemed to be scanning her social media as though it would somehow make everything more clear, more real, or maybe we simply hoped that she would display remorse and set our angry souls to rest. She said she was grateful for her safety and that of her infant daughter, who had been in the back seat. She was glad to be home, unharmed, with family. She did not mention my father or even that anyone else had been involved. She did not mention that the accident had been her fault. She has never reached out to ask about him or to apologize for the agony my family has endured. This was not her first reckless driving incident. We have mutual friends.

Sometimes I want to send her a letter. Sometimes I want to contact the school she works at, and warn them that if she does not have her morning coffee, she might hurt someone. I don’t do these things. Mostly, I hope that she takes her time now. I hope she is a good mother, wife, friend, teacher. I hope she offers the world more these days because she feels the gravity of life, and that she knows what she stole.

My parents were not like most parents. They really and truly loved each other, and not in that way that comes from being dependent upon one another or from having lived together for a long time. It was that ‘in love’ love. They held hands. They played badminton in the back field in their bathrobes. They went away for weekends to romantic cabins. They lived in a one-room studio home in the barn they had renovated. They read out loud to each other. They listened to operas and cried. They looked at each other with mushy doe-eyes. Not that they were perfect, of course. My mother could sigh and he could groan and they could both roll their eyes and snap at one another. But my parents were absolutely bonkers about each other all the same.

My father had just announced his retirement. He would only be working another six weeks, he said, and they would finally get to enjoy the time they’d been waiting their whole lives for. They talked about selling everything to live on a sailboat while they still could, roving the Chesapeake Bay once more. Or staying on the farm and planting an orchard. They were full of dreams.

Before the accident.

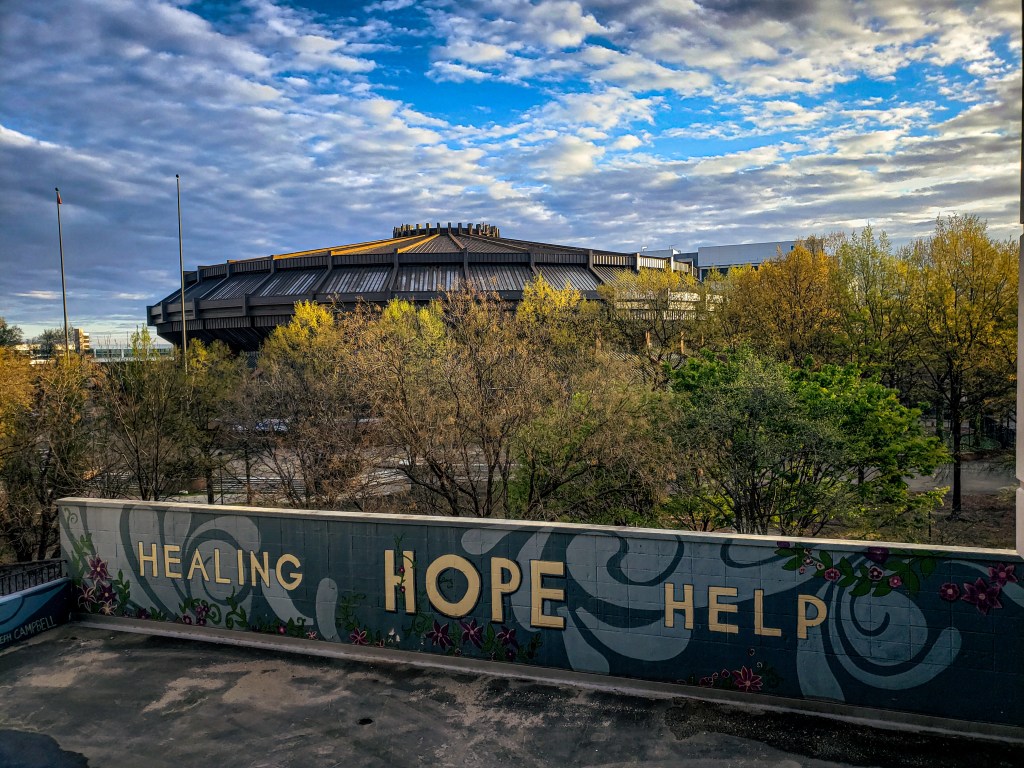

Initially, VCU provided my mother with a small but serviceable hotel room down the street from the hospital. A few days a week, students from their campus made dinner, and from her door you could see a mural with the words, ‘Healing, Hope, Help’ writ large. My mother joked that the people in neighboring rooms might think her a madwoman, because she had screamed, cried harder than she had ever cried in her life, flung herself about in a rage, and laughed uproariously all in a ten-hour span. I thought each of these rooms had likely seen similar fits. They were capsules of grief.

From there, she moved to a tiny red house owned by a friend of a friend of my grandmother’s. We called it The Princess Pagoda. The woman who owned it had decorated it with swaths of exotic fabric in a riot of colors. There were stained glass windows featuring doves and sun rays and green grass. There was a lovely little shower and soaking tub. We shared a bottle of wine in the garden there, and wished it was a vacation.

A dove sat on a nest outside the kitchen window, her babies stowed away under her wings. My mother dried her hair and put on her makeup and cried while ‘their song’ wafted from the shuffled Pandora station. We walked the downtown area and gazed at the water and Victorian architecture and the pig statues that stood on each block. Later, we discovered that one had to become a contortionist to wash one’s hair in the little tub because the shower head was only decorative, and the whole place was infested with brown recluse spiders.

It was on to another hotel, an even more temporary affair. The price was not cost-effective.

Trying some different smells to encourage cognition and memory.

Then a motel that smelled of fish, immigrant spices, and marijuana smoke. We cooked salmon on a hot plate and ate olives at a table just big enough for two chairs. My mother learned where to avoid once night fell and found a little stretch of beach nearby where we had a seaweed fight with the girls and threw a frisbee back and forth. There was a YMCA nearby, and my mother tried to establish a routine, attending water classes. I think this was more to wear herself out physically so she could sleep at night than anything else.

Her next-door neighbors woke her up at all hours screaming. She learned new and creative curses. We rode the elevator with those neighbors, a couple with a young boy holding a drumstick ice cream cone. His mother told him it looked like a penis and his father knocked it out of his hand and onto the ground.

“Fuck you,” the child yelled, and snatched his ice cream up like it was the most normal thing in the world.

My Mother has no ability to mask her expressions. A rapid play of horror, shock, interest, anger, and then the vapid, friendly smile she fell back on in situations of stress danced across her face like a robot short-circuiting.

Another elevator companion wore plastic hospital booties over her adidas slides, and two pairs of socks were tucked over her sweatpants by degrees. A hood was cinched tightly over her face, and her hands sported rubber garden gloves. Three surgical masks were layered over her mouth and nose, and a pair of wide goggle glasses hid her eyes. She dragged a suitcase behind her with each zipper tab swathed in saran wrap.

A knobby-jointed woman lived in a van outside, and two men came to visit her regularly. Most of her teeth were missing. The women in the lobby were delightful, loud, and eager huggers. They knew my mother by name and asked after my father. When it was time to move on again, they were sad to see her go.

Home didn’t exist for my mother anymore. Only my father existed, day in and day out. She made his meals, advocated for him when she needed to, which was a lot, and made decisions she never thought she’d have to make alone.

***

Four months and many moves after the accident, he was in The Laurels, an assisted living and rehabilitation center. My sister-in-law Mariah works there, and it was only seven minutes from their home, so my mother could move in with them.

On this particular day, I had come for a visit, and my mother left to run errands. My father slept on and off while I worked in the chair beside his bed. We talked when he wanted to. Some of it made sense and some of it didn’t. When his diaper needed changing, I called for a nurse. By the time she arrived, his clothes were wet, and by the time she had his diaper off, she realized she was out of trash bags. I had one in my bag for her. This was old hat by now. The bed was also wet, so I helped her lift my father and remove the soiled linens. She discovered that she was also out of replacements, and those I didn’t have. She stood there, unsure of what to do next.

“You can go and find some. I’ll stay with him,” I said.

“Are you sure?” she asked.

“I’m sure.”

She looked relieved. They were understaffed and over-worked.

My father lay on his side, arms and legs beyond small, the skin bunched at the elbows and armpits. His grey, non-slip socks were rumpled around his ankles and backwards. The adult diaper he wore hung wrinkled and loose on his emaciated frame. The navy-blue mattress beneath him had a stain in the middle. It wasn’t from today. It was months’ worth of stains in jagged circles, a tie-dye of brown rings, radiating outward in a melted sunburst from dark to light. Some other human being had lain here before him, pissing and shitting and vomiting. It reeked. My father tucked his legs in a little, his arms folded over his abdomen. He wanted to curl tighter, but he was too tired, his breath a series of sighs. His eyes were sad and confused and beyond humiliation.

“I’m cold,” he said quietly.

I sat on the edge of his putrid nest and put my arms around him, rubbing his back gently. He didn’t know me. All he knew was that his life was not what it should be. I loved him and missed him, my bog body of a father. The year had blended for me, coming full circle. Those things in their glass boxes at Ireland’s Museum of Archaeology were no longer alien. They were lodged in my heart. They, like my father, were once here in a glorious fullness of being. My father, the academic outdoorsman, who devoured books and could more easily and happily discuss quantum physics and world religion than he could the weather. The one who could run for miles only to leap into the arms of a tree for a round of pull ups at seventy-four years old. The one his grandchildren called ‘Exalted Grandfather’ and ‘Slash, the Warrior Cat.’ The one who wanted to live like old Caleb from the book of Joshua, who asked for the mountain of giants while younger men sought gentle valleys.

A patient across the hall yelled, “I like my coffee like I like my women: bold, black, full-bodied! Wait staff! Wait staff! I demand raspberry sorbet! I want it on my bedside table! Reset! Reactivate!” The moment was viscerally real and cartoonishly ludicrous all at once.

***

A month later, my father sat in his wheelchair eating a slab of pork and a side salad for lunch. He used to avoid pork, but now he hacks away at whatever lies before him, stuffing large portions into his mouth.

“This has a savage amount of fat,” he said finally, looking dismayed. “And this salad has iceberg lettuce. How did it become such a taste? It’s awful. It never truly became anything of value. Its life has no meaning at all.”

One of his doctors knocked and entered, doing his rounds. He asked my father for our names in a sort of memory and conversation exercise. My father pointed to me.

“This is Savage Fat,” he said. “I’m Iceberg Lettuce.”

I almost spit out my water, laughing. His doctor did not understand the joke.

Looking back, I found the whole thing less funny, and wondered if my father truly felt like his life had no meaning at all. I took to telling him that he was not at all like iceberg lettuce, and he would smile and say,

“Thank you. That means a lot to me.”

***

I should mention that the blue mattress was removed from his room, brown fluid pouring from its seams as it went. Mariah made sure a brand new one found its way there. This was not her fault. Everyone was doing the best they could. The janitors, CNAs, nurses, nutritionists, therapists, doctors – they all did their best, and their best was excellent. None of these places are capable of being perfect. You can’t expect them to be.

If you or a loved one is ever in need of their services, you won’t be perfect either. You have to be present and on top of medications, diet, diaper changes, and schedule. The system will not do it all for you. I know you’re probably tired and overwhelmed but do it anyway. My five foot two inches tall, sixty-nine-year-old mother did. Most of the time, she caught more flies with honey, but sometimes she had to be a ‘lioness’ to quote my father.

They are both home in their one-room barn now. He can shuffle unassisted across level surfaces. He can manage most of his own hygienic care. He knows who I am but not always how old I am or where I live or who I’m married to. He is more loving than he has ever been, and he cries easily. His impulse control is limited, which can be both frustrating and humorous. He prays for healing, especially for his mind and his blind right eye. Sometimes he puts in the work and sometimes he wallows so deeply in self-pity that he refuses to leave to couch. He knows he is different than he was, and he worries that what he can contribute to the family, and especially to my mother, is not enough. He tells the same stories over and over with great intensity. He can tell me about Meso-America, but he can’t remember the password to his laptop. He can give a whole sermon on Greek and marriage but can’t problem-solve his way through current issues.

He’s spoken of a desire to run out of the house and go to the ocean to swim forever with my mother, the woman he loves. He’s told my mother to abandon him or to take him out to the field to shoot him like a pet that can no longer lead a good life. He has learned to hug again but will never drive again. He has said that his mind is a dangerous place. If he doesn’t know what he’s looking for when he goes inward, he can become lost, and he doesn’t want to be lost in a bad place full of holes.

My parents have a court hearing coming up in an attempt to achieve some financial compensation on a variety of fronts. My father told me,

“We’ll go, but I’m not prepared. I don’t know what to say or what to do or where to sit. They’ll ask me questions, and then they’ll tell me that I’m stupid and send me home. I don’t want to go.”

I wish I could help him. I wish I could have told him not to drive to work that day in April, and instead to stay home with his beautiful wife and go for a hike like he’d wanted to. Savage Fat is very tired today.